The Advocate and the Defender Part III + IV

By Sara Ganim

Part III

“Hey, brother.”

A voice echoes through the cracks of Dekraai’s jailhouse sink as he sits hunched over his bowl of lukewarm ramen.

“Hey, do you need hot water?”

Dekraai peers up and looks over. He’s just been moved to cell 3 of sector 17, module L — a psychiatric evaluation unit in the processing hub known as the Intake Release Center.

L Mod of Tank 17 has 16 cells: 8 on the top, 8 on the bottom. They wrap in a semi-circle around the guard station. The guards are uniformed sheriff’s deputies, but in this mod, there are other officials too — nurses and mental health professionals. Because Tank 17 is where people with medical histories are often sent.

Dekraai’s cell has only one neighbor, and the guy seems really eager to chat. Dekraai knows he’s about to spend a lot of time in isolation. His blue armband signals his total separation status. So, he figures, why not?

“Brother, I saw you’re limping. Do you need anything?”

This unexpectedly warm outreach is coming from a 30-year-old member of the Mexican Mafia. Dekraai isn’t sure what his deal is exactly, or what he’s in for, but he notices that he seems to have this place figured out. He sees him each morning, making rounds, asking fellow inmates if they need help. Dekraai notices he has a white armband, which means that he has a lot of freedom.

“I got a piece for you.”

The voice reverberates through the pipes.

“You shave down a spoon, a plastic spoon. Stick the piece inside the hot water button so it’ll stick.”

“Try it, brother,” he says.

The sink rig is game-changing. Not only does he have hot water for coffee and for noodles, but he can do what inmates call a “bird-bath” — using the sink to shower.

“It’s survival,” his new friend opines.

“Thanks a million,” Dekraai responds.

Dekraai doesn’t know much about this seemingly benevolent new friend. But the friend knows a lot about Dekraai.

“How old is your son?” he asks.

Dekraai hesitates.

“I’ve seen you on the TVs in the dayroom.”

“Dominic is 8.”

“Dominic? My daughter is Dominique. Wow, that’s cool.”

Over the next few days, Dekraai continues to talk, more and more, opening up about why he did what he did. Reality is setting in. Not regret, but a realization. These four walls are the rest of his life. His son, who he was supposedly fighting for, is basically an orphan. His new wife, who he so strongly defended, will probably leave him. His revenge has backfired.

“You need to cope with it, brother.”

This new confidant has an unexpectedly empathetic ear. He even goes into his collection of books and gives one to Dekraai to help him pass the time.

Dekraai opens the cover and sees his new friend has signed it with his street name: Wicked: Insane killer, south side.”

Dekraai is so grateful that he promises to transfer some cash into the guy’s inmate account.

“It’s comforting,” Dekraai says. “You’ve been really cool.”

“Yeah, of course, dude,” Wicked replies. “We’re here. We’re on the same side.”

Years later, in court, Wicked will be asked by Dekraai’s attorney, Scott Sanders:

“When he said that to you, was there a part of you — just a part of you that thought, boy, this guy really trusts me and I feel like, on some level, I’m taking advantage of that trust? Did you feel that way?”

“A little bit,” Wicked replies.

Because they might both be on the inside, but they are not on the same side.

Scott Sanders learns about all of this from prosecutors who seem pretty nonchalant about it.

“We don’t plan to have him testify,” one says. “What Dekraai said speaks for itself.”

Scott rolls his eyes. He knows what they are trying to do. Prosecutors think that if they aren’t going to have “Wicked” testify, then Scott doesn’t need to know who he really is. Instead, they’re just calling him “Inmate F.”

Their righteousness makes Scott seethe.

Cathy knows he’s anxious to get his hands on the transcript. She is nearly out the door on a Friday evening when she sees that new discovery has been dropped off. Among the files, there’s a compact disc. She knows it’s likely those jail cell recordings.

She walks out the door anyway.

And then she turns around.

Weekends be damned.

She drops the CD into a drive and waits anxiously as the flimsy little disc drawer sucks back into her computer tower. She yells over to Scott as she prints out paper copies of the transcripts and accompanying notes. They each take half of the stack and begin reading.

“Hey brother …”

… “Dominic? My daughter is Dominique.”

“You need anything? …”

“. . .You’ve been really cool.”

Something isn’t right, but Scott cannot put his finger on it. Yes, informants exist. Yes, they can be a useful tool. But there are rules. And Scott has no intention of taking the prosecution's word for how this all went down.

He leans back in his office chair and stares at the stale, depressing walls. The office is a four-story cement building with fixed angled slats and no traditional windows. It has almost no natural light. It used to be the county morgue, until the Orange County Supervisors put the least-appreciated public servants there instead. But that doesn’t bother Scott. He does some of his best work in the dark.

It’s late on a Friday night in April 2012, about six months after the shooting.

Scott drops the papers onto his lap in frustration.

"This is complete bullshit,” he says to Cathy.

Scott is not a loud guy, but he is emotive. He doesn’t need to raise his voice to be compelling. Instead, he goes deep and slow. His midwestern accent heightens.

“Not a chance in the world this was anything other than a complete set-up.”

True believers like Scott are always on high alert for cheating by prosecutors and law enforcement, but catching — and then proving — anything nefarious is rare.

Scott’s eyes race through the words he’s reading. His pulse and his body temperature are rising with every sentence he scans. The outrage is punctuated with another feeling — familiarity.

Scott stops.

Cathy looks up at him.

“What is it?”

There is one place where prosecutors have slipped up and referred to their secret informant by his partial name: “Fernando P.”

“Oh my fucking God,” Scott erupts. He gets up and goes straight to the wall of boxes of black binders where his other major case — against the actor Daniel Wozniak — is stored.

Scott begins leafing through Wozniak documents, knowing that this case also has an unnamed jailhouse snitch.

He finds it.

The secret informant in Dekraai: Fernando P.

The secret informant in Wozniak: F. Perez.

Scott runs back to his computer. He types in the amalgamation of the two: Fernando Perez. There are dozens in the Orange County court system. But only one has an entry for a transfer to federal court to testify.

“What are the chances of that?” Cathy wonders aloud.

“There’s no fucking way this is a coincidence.” Scott is far less measured. “Holy fucking shit.”

He goes back to the files. He’s searching for the scribbled notes that were handed off to police by the informant in Wozniak’s case. He lays it side-by-side with the handwritten notes from the informant in Dekraai’s.

“It matches exactly,” Cathy says, hardly believing what she’s seeing.

Scott is no longer sweating or shouting. He’s calm. Collected. He can feel the importance of this moment. There is just no way that this one inmate keeps coincidentally stumbling into so many of the county’s highest-profile defendants, getting them to confess their crimes, without any help from prosecutors.

“This is huge,” Scott says. “We’re going to expose these guys for what they really are.”

Scott pauses. Cathy looks back, waiting anxiously for him to finish. The word comes out heavy, dripping with the years of frustration Scott’s endured from prosecutors who were just a bit too smug and righteous.

“Cheaters.”

Fernando Perez was 15 when he joined the Mexican mafia. Young and trying to make a name for himself, he adopted the hurt-or-be-hurt mentality both on the streets and inside Orange County jail.

Officially, his rap sheet shows that he was selling drugs, carrying illegal guns, getting into fights to prove himself. Unofficially, he was a shot-caller, a leader of his mesa, extorting enemies and putting people on a hit list called “hard candy.”

It felt good to be in power, to be — his gang name — Wicked. But Fernando had a nagging feeling that he was in a life that he really didn’t want to be in. In the SoCal circles he ran in, a young Hispanic man had to make a choice: You were either with them, or against them. Fernando chose to be with them.

By 2009, he’d hit his three strikes — California’s notorious law that says that once you rack up three felony convictions, you go away for life. Sitting in his cell, he knows that he’s not going to see much of his kids now unless he figures something out.

So he starts writing down what he knows. Extortion is a currency on the inside, too.

He pens a letter to the judge in his case, reflecting on a life full of mistakes, as he puts it. “I’m truly sorry for what I’ve done,” he wrote. “I’m facing life for sitting in a vehicle with a gun in which no crime was committed.”

“Your honor,” he writes, “Fernando Perez is not a bad person. I’m a family man that would love to see his kids grow up and live a productive life. I’m asking, Your Honor, for one last chance to show that I will be a productive citizen of the community.”

Fernando has a buddy, he goes by the name Camel, who also wanted out of the life. Camel went into protective custody after leaving the mesa. But before he vanished, he told Fernando what to do.

“Man, hey,” Camel writes to Fernando from another prison, “you know it’s not all that bad on this side.”

Some may see a genuine epiphany, others pure desperation. Whatever the motive, Fernando Perez is realizing that his life so far has been meaningless and he’s now destined to rot away from the inside of a concrete and metal cell.

He recalls how, back in the late 90s, he’d given information to a prosecutor in Anaheim in exchange for some leniency. It worked back then. So he decides to try it again. He reaches out to the special handling unit. Everyone in the jail knows that if you have information to share, that’s who to tell.

It isn’t long before Sheriff’s Deputy Ben Garcia, of the Special Handling Unit, quietly pulls Fernando into a meeting. He shares some papers that explain the rules. There’s language warning that there are no guarantees — no promises being made. Fernando signs. His red armband — indicating that he’s a hardened criminal — is changed to white, signaling to guards that Fernando is a cooperator. Suddenly, if he asks for more dayroom time, he gets it. If he needs to make a non-collect phone call, sure. If he needs to get a note to Garcia, no problem.

“You can’t ask questions,” Garcia warns him. “But if they do talk about their case, you can go ahead and write it down.”

The assignment comes with potential benefits. It’s unspoken, but known, that cooperation will be considered when it comes to sentencing. But there is also a warning.

“Don’t ever lie to me,” Garcia says. “One lie, and that’s it. All I want is the truth.”

People like to brag in lockup. Fernando takes his job very seriously. A potential to restart his life is on the line. He starts making rounds on his block every morning, checking on folks, asking if they need hot water for coffee, or anything else that he can help with.

Back in his cell, he begins to scribble it all down. Some of it is ghastly. Some very, very detailed.

“And they just kept talking,” he tells Garcia as he passes off the notes.

In July of 2010, shortly after being moved to a new block, Fernando gets his first big scoop. He sends a message to Garcia — “this dude just basically spilled his guts and told me about the gruesome crime” — who sets up a meeting with Costa Mesa police.

“This guy is a fucking creep,” Fernando tells detectives. “He set up his friend and cut up his body and all this stuff.”

The guy is Daniel Wozniak — the budding actor accused of an elaborate plot to kill his neighbor for money by staging a murder-suicide and luring in another innocent bystander.

The crime is bizarre. So a confession from Wozniak is a really big deal to prosecutors. Garcia’s colleague in the special handling unit, Bill Grover, tells Fernando to “marinate the Costa Mesa info.” Basically, see what you can get out of him.

And that’s how Wozniak’s alleged confession to “F. Perez” lands in a box in Scott Sanders’ office.

Of course, there are rules for due process. Two of them are significant to this story: First, the Constitution says that a defendant cannot be interrogated without the chance to have their attorney present. This is not just about police interrogation, but anyone doing any kind of questioning as an arm of the prosecution. That includes informants. And second, if an informant captures a chance confession that prosecutors plan to use, they also have to give the defense any evidence about the informant — including anything that might discredit them. This is part of a process called discovery. Basically, prosecutors should be an open book. No surprises.

But prosecutors downplayed the Wozniak confession. They said the informant wouldn’t testify or be part of the case. There was seemingly no reason for Scott Sanders to flag it as a big deal.

Until months later.

Fernando Perez comes back from a shower and sees Scott Dekraai sitting at a desk in his cell, head in hands.

“What’s up, bro?” Fernando asks.

The friendship is no coincidence. Three days after the shooting, Fernando is moved into the cell next to Dekraai’s. Two more days after that, Fernando slips a note to Garcia. A meeting is called. Prosecutors and law enforcement sit around a table with Fernando. It’s a familiar scene. They’ve all done this many times before.

“How long had you known him before this conversation?” someone asks Fernando.

“Probably, like, two days,” he replies.

“What did you talk about?”

“Nothin’” he says. “Nothing much, just, like, just kinda, keep trying to get comfortable with him to see if he was really, you know, crazy.”

For whatever reason, prosecutors are worried that Dekraai might try to wiggle out of the death penalty because of his psychiatric issues, even though Scott Sanders has never indicated that he plans to pursue an insanity defense. Regardless of the reason, law enforcement wants more from Dekraai. They want more than his taped confession to police. They want more than all the evidence that placed him at the scene.

“Maybe we can wire you up,” a deputy prosecutor suggests in the meeting with Fernando.

“Nah, we can’t wire him,” a sheriff’s deputy jumps in. “But we can wire Dekraai’s cell.”

Over the next few weeks — until Dekraai is moved on October 25 to a different facility — 130 hours of recordings are collected.

Scott!

Yeah.

Good morning, brother.

How you feeling this morning?

You sleep well?

The full details of what they said to each other were never made public. Only small excerpts will emerge.

So what are you thinking about, buddy?

I’m just reading this book.

Oh, you’re reading?

Yeah. How about you?

Is it pretty good?

I’ve got a good one over here for you.

Huh?

I’m gonna give you another one

Scott is euphoric, but he doesn’t tell anyone what he figured out that Friday evening with Cathy. For months, he plays dumb in court and in front of prosecutors. He knows it is notoriously hard to win the argument of prosecutorial misconduct. Judges often give prosecutors the benefit of the doubt, prioritizing the appearance of justice for victims, even when the rules are bent or broken. As a result, serious violations are frequently minimized, overlooked, or dismissed as harmless error. True believers like Scott also tend to believe that judges — many who are former prosecutors themselves — give a lot of runway to prosecutors.

But this is a once-in-a-career chance to try.

So Scott begins to put together a motion challenging the Dekraai case based on a violation of the Sixth Amendment — arguing that the government has deliberately circumvented Dekraai’s right to have an attorney any time he’s questioned by authorities. To Scott, this isn’t just a legal technicality. It’s a clear, calculated breach of constitutional protections.

And pretty quickly, Scott also realizes that this might be even bigger than just Dekraai. As he combs through Fernando Perez’s court record, Scott sees that he’s been waiting way too long — about two years — to be sentenced for his third-strike offense. And, in the meantime, he’s being transported to different courthouses for unspecified reasons.

“This isn’t a one-off, or a two-off,” he says. “He’s a professional snitch.”

That’s strange, Judge Goethals thinks. I’ve never heard of a jail cell being wired.

The debate over Fernando Perez starts out simple. Scott Sanders just wants prosecutors to fess up to who this guy is, how many times he’s been an informant, and what he’s getting in return for his intel.

He files a rather simple motion in January of 2013, asking for the details of his background. Scott is playing things close to the chest. He knows more than he’s letting on. He wants to see if prosecutors will hide things from him.

Dan Wagner, one of the lead prosecutors, pushes back. He argues to Goethals that there is no reason to prod when the informant won’t be getting any special treatment. His pushback is over-the-top, theatrical even. Goethals is annoyed by the tantrum he’s throwing in court, but he chalks it up to a performance for the victims and media in attendance.

“That’s not the law,” Goethals reminds Wagner. He orders him to hand over Inmate F’s identity.

“You have 15 days,” he rules.

What Goethals doesn’t know is that, not only does Scott already know Inmate F’s identity. Two months ago, he went to his house.

Knock, knock.

A woman appears. She’s kind, welcoming.

“We’re looking for Fernando Perez,” Scott tells her with a small smile.

“He’s not here, but I am his mother.”

She invites him in.

“He’s not in trouble,” Scott assures her. “I just want to ask him about a case that he’s part of.”

The woman hesitates. She asks if she can have a moment to check something. When she returns, she tells him that Fernando isn’t there, but she cannot say anything more.

As the door closes behind him, Scott is left doing the process of elimination. If he is not in custody and he’s not at home, obviously he’s being hidden.

In February, the documents on Fernando that Scott and Cathy have been waiting for begin to arrive. Prosecutors first send 45 DVDs and nearly 5,500 pages of information, and then follow it up with even more, eventually doubling the number. It’s more than 9 boxes of paper — piled up and waiting to reveal itself.

And it all boils down to this: Scott Sanders' hunch was right. The materials show that Fernando Perez had worked 8 Mexican Mafia cases, before Wozniak and Dekraai.

He was, in fact, a seasoned snitch.

And keeping that secret is a huge judicial no-no.

But things are bigger than Fernando Perez. The reason there are so many more pages in this document dump is because there are dozens of other informants like him who have been working cases for the prosecution from inside the jail for many years.

Scott and Cathy start digging in. They find hundreds of pages of handwritten informant notes from Fernando Perez and another longtime informant named Oscar Moriel. The two are using gang monikers and Scott has to decode them to figure out how many cases have been impacted by this secretive system.

One of the notes, written by Moriel, explains their tactics. They’ve coined it the “dis-iso scam” — short for disciplinary-isolation scam. Basically, to better the chances of getting good intel, informants are moved to isolation in the same area as targets — like Dekraai, who was suddenly moved into a cell next to Fernando Perez. Of course, criminals wouldn’t expect to find informants in the jail’s disciplinary isolation sector.

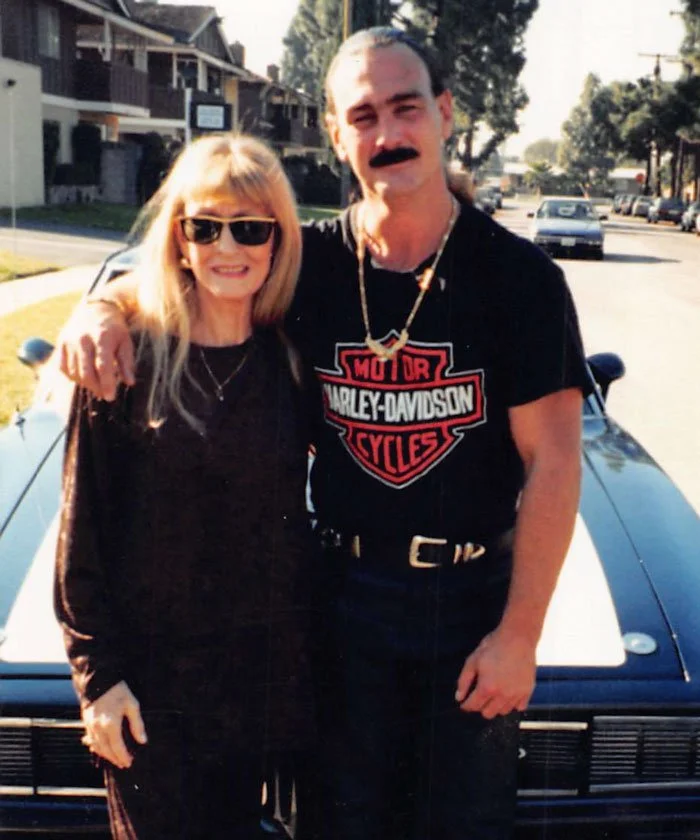

Handwritten notes from informant Oscar Moriel. Credit: Scott Sanders

Oscar Moriel and the police working with him are comfortable enough with their scam to give it a nickname. And to openly talk about it in notes. It’s clear to Scott that this is a violation of the 6th Amendment, which says that government agents — or informants working as government agents — cannot question charged inmates about their crimes. No wonder prosecutors didn’t want to turn over their snitches’ names. If they had, it would have been obvious that they weren’t coincidentally befriending their targets.

“These notes prove it,” Scott tells Cathy. “They show just how often defendants were being defrauded.”

Scott begins ordering hundreds of thousands of pages of transcripts and exhibits from cases he knows these informants had worked. In one of them, he finds that prosecutors hid 200 pages of handwritten notes by Oscar Moriel from the defense of a boy charged with attempted murder at just 14 years old. In those notes, he finds plenty of evidence that police locked up the wrong guy, but prosecutors never shared that with the defense team. They hid it, and they claimed that Moriel just stumbled into this kid in jail. In fact, it was meticulously orchestrated.

Scott is horrified, but he’s also thrilled. True believers always suspect misconduct. But this injustice is so much worse than he thought, but he’s undeniably excited that he’s unravelling something so deeply entrenched, so systemic, that exposing it could potentially stir up dozens of cases that penetrate years of status quo in the county’s justice system. Cathy calls it “demented excitement.” Uncovering the truth feels like unease wrapped in vindication. It isn’t pure joy, but it does bring the kind of clarity that comes with finally understanding what’s really been going on.

Scott starts working on two motions: One to remove the Orange County District Attorney’s Office from Dekraai’s case, and one to dismiss the death penalty.

Scott is waking up as early as he can, staying at work as late as he can, but that’s not cutting it.

“Where are you going?” Cathy asks one day, as he packs up in frustration.

“Too many distractions. Too many people asking me for things.”

Scott makes an unofficial-official request for some vacation time, but he doesn’t go home, either.

He needs total focus, along with sustenance, of course. So he starts getting to Denny’s at 2 a.m., right as they open, switching to Starbucks at 430 a.m. when the first coffee pot is brewed. When it feels like he’s overstayed his welcome, he finds another local coffee shop.

It starts as 18-hour days, but they begin to bleed together.

Time commuting home is time away from writing. So Scott just sleeps in his car, much to the chagrin of his wife.

“You’re out there looking like a fucking homeless guy, sleeping in the car,” she tells him. Normally, Priscilla is all-in on obsessions over cases. But this feels extreme. “You might not care, but that represents all of us. Me, the kids. Not just you.”

Scott Sanders asleep in a car after a long night of writing his motion. Credit: Cathy Ware

Cathy is growing annoyed, too. At first, she thinks the shenanigans are comical and, of course, admirable. But Scott is piling on the paperwork. He’s asking for thousands of copies of transcripts, calling at all hours, falling asleep in her car.

There are moments of levity. Every few days he shares his latest rap song — original lyrics lifted from the documents he’s reading. He’s wearing his hair longer now, down below his ears. There’s more gray in his beard as he shuffles down the halls of the office, dancing to his latest composition.

Lyin’ snitches. Every single day.

DA to the judge — “believe what they say.”

Scott does a little wiggle, squints his eyes and pivots on his heels.

What about that justice they love to mention?

Blindfolded lies. All they want's your confession.

He stretches out “con–fess-ion” in a high-pitched squeak. Then he notices that Cathy is recording him and he bursts into laughter.

But it’s all incredibly stressful.

“You are driving me to the grave,” Cathy says. It’s in jest, but not really.

There’s barely anyone else to lean on. Scott can’t afford for any of this to leak before he finishes his motion. He trusts few. Even in his own office. The chatter around him is obvious.

What is taking him so long?

Why does he get an entire year to write one motion?

Scott can see that he is straining his people — the ones he needs most. But there is a bigger problem.

Three years before Dekraai’s murderous rampage, California passed Proposition 9, also known as Marsy’s Law, which gives victims and their families a robust suite of legal rights, including the right to speak at all court hearings. While typically, in other states, victims are mostly silent until trial or sentencing, in California, they are an audible part of the process.

And Paul is happy to take advantage of that. He’s more than fed up with the delays. He sees absolutely no reason why a case with so much concrete evidence should be slogging through the system. He feels he’s been more than patient, watching yet another year turn over without progress. Each time he shows up in court hoping for justice, he finds nothing more than deferrals.

He doesn’t care at all when he listens to Scott Sanders opine in court about the meaning of justice, or how fair and due process is meant for everyone, regardless of the crime. He doesn’t understand when Goethals sides with Sanders and makes prosecutors turn over more evidence. After all, to Paul, it’s not about the informant. It’s about the information he collected.

“We’re approaching two years,” Paul says, as he stands before the court in August 2013. His anger is not directed at the judge, or even at Dekraai. No, today, he goes directly at the one person he holds responsible for the delay of justice: Scott Sanders.

“The damage this does to my family on a daily basis is amazing. I want you to understand that. The fact of the matter is that we are approaching two years and we’re only this far along, and this could approach another two or three years, and I’ve got to sit in that chair and relive that day over and over again. It’s not acceptable to me, nor should it be acceptable to anyone in this room.”

Goethals watches from the bench. He feels tremendously for Paul, and everyone else who was irreparably broken on October 12, 2011. He could shut all this down now, if he wanted to. He could give Scott a deadline. He could force things to move to trial on the timeline he’d originally planned.

But Goethal’s oath is to the truth. And he’s intrigued. He wants to see what “Crazy Scott,” as they’re calling him, is unearthing.

It will be five more months before Scott finally stops writing up his findings. Cathy has to print everything three times — one for the prosecution, for the judge, and for the court. She spends days at the copy machine.

The final page count on the motion is 505 pages. Plus, 15,000 pages of exhibits. It’s the largest motion in California history, and — considering that most courts have a cap around 45 pages — likely the most substantial such filing in the history of United States court systems.

Judge Tom Goethals is returning from his daily run.

He’s a slight man, average height. Square jaw. Face like he’s seen the world. In truth, he’s born and raised here, but no one could say he lacks measure or wisdom.

Since the start of his career, he’s taken the noon to 1 p.m. hour to run along the banks of the Santa Ana River. It’s where he finds clarity for hard decisions — although this isn’t yet feeling like one. Today, Goethals is content, thinking about the beautiful winter day.

As the hour ends, he returns to the Superior Court of California, County of Orange. It’s a rather ugly building. Two giant black boxes with sterile cement exterior columns stacked on top of each other. It’s a typical 1970s-era building, although technically finished in 1968.

But from Goethals’ chambers on the eleventh floor, the perspective shifts. Looking outward, the view is striking, a panorama that softens the building’s brutalist shell. He slides the key into the lock, pushes against the door, only to find it barely opens. Something on the other side is blocking his way.

It’s a push cart, the kind used for Bankers' boxes, and usually reserved for trial days, when literal cartloads of evidence need to be wheeled around.

Today, there is no trial scheduled. But it is the day that Scott Sanders has delivered his epic motion in the Scott Dekraai case. Goethals doesn’t know that yet. He looks at the cart, with three shelves completely full of black 3-ring binders and shouts to his staff.

“What the heck is this?” he asks his longtime clerk, thinking perhaps she was moving files and forgot about it.

“Oh, no,” she replies. “That’s a motion on Dekraai.”

“What the…”

Goethels has never seen a motion like this before.

“God in heaven,” he mutters. “What is all this?”

He takes the binder labeled “1” and opens it up. The motion is, as he later puts it, “awkwardly titled: Notice and Nonstatutory Motion to Dismiss the Death Penalty; Points and Authorities in Support Thereof; Exhibits and Declaration of Counsel.” The other 30-some binders are all exhibits.

Goethals sits at his desk, opens the binder, and begins to read the first 100 pages or so. His initial reaction?

“This doesn’t make a whole lot of sense.”

He knows that Scott has been in the weeds on this for a year. He knows that he must have read it 20 times over. He also thinks he could have benefited from an editor.

“Oh, come on,” he says aloud, and slams the binder shut. “It’s a bit hyperbolic.”

In his head, he’s thinking, yeah, maybe there is something there, but a lot of it is stuff that doesn’t even impact the Dekraai case.

Years later, he put it like this: “I'm on page 386 and he's talking about these other cases that had happened years before. It wasn't written so that it really just jumped out at you as being so obviously applicable.”

Goethals knows that misconduct happens. But in his mind, “sophisticated lawyers and sophisticated judges know that this doesn't happen a lot.”

The press reacts with similar skepticism. The LAist highlights the audacity. The Los Angeles Times captures the widespread cynicism. Voice of OC frames Scott Sanders as theatrical. Wagner calls the allegations “scurrilous” and filled with untruths. Rackauckas says Sanders is drumming up a false narrative of conspiracy.

From Goethals’ perspective, it’s simple: Sanders says that prosecutors are engaging in the most widespread cheating ever uncovered, and prosecutors say Sanders is crazy.

“Let’s see who is right,” he says.

Scott Dekraai (L), accused of killing eight people in a Seal Beach beauty salon, listens with his attorney Assistant Public Defender Scott Sanders (R) during a motion hearing on March 18, 2014 in Santa Ana, California. Credit: Mark Boster-Pool/Getty Images

He calls everyone to court to inform them that a hearing will be held. From the bench, he explains that he believes the law demands he let this play out.

Paul Wilson steps up to speak. He’s done more than read the news reports. He read the motion, too. He’s flown in from Arizona, where he’s temporarily living and working. And he has no tolerance for this nonsense. None at all.

“Every time there is one of these, what seems to us as — and excuse me — an insane motion filed, we have to appear in court. It’s just taking an extreme toll on all of us.”

The words ricochet around the room. He goes on.

“Having to look at that —

He glares at Dekraai, who sits stoically in his orange jumpsuit.

“— and know what he did to my family.

Paul feels like he’s watching himself in a movie. The room spins. He’s nearly blacked out with rage.

“Week after week after week, and not progressing with this — we are approaching three years. This is — this is killing us in more ways than one. And I ask that the court take that into consideration when we have to be continually called back into this courtroom.

Goethals jumps in.

“What would you like me to do?

Paul is smacked back to reality. He stands there silently.

“Mr. Wilson?”

Still nothing.

So Goethals takes a breath and gently begins to speak.

“Let me interrupt you for a second. What is your thought about the significant legal issues that are involved in this case? Would you like me to just ignore them so that the court, if it results in a conviction, is reversed and you are back here in five or ten years?”

Paul’s shoulders relax. His head hangs for a second.

“No, sir —”

“— to do it all over again?”

“No, sir —”

“You don’t want me to do that, do you?”

“No, sir. I do not.”

Paul stumbles around a sentence about how he is not well-versed in the details of the law, but then straightens out to make his point.

“It seems that we’ve just gotten so far off track of what this coward actually did and what we are here for.”

“Well, I haven’t lost focus of what the issues are here. But the issues are, from a legal standpoint — “

“Yes”

“— unfortunately complicated.”

Goethals goes on to explain to Paul, and by default, to the whole community, that he’s going to hold a significant hearing on what he sees as an “unusual issue.”

“I have not seen, in 35 years, an issue exactly like this, from a legal standpoint. And the fact that it relates to this defendant’s case doesn’t change it.”

He warns Paul that things are going to take time. It’s going to continue to feel like it’s dragging.

“You labeled this an insane motion. And from your perspective, I don’t blame you for thinking that.

“Thank you.”

“But I have a sense from the defense, especially recently, a sensitivity to the fact that they believe that you all think that they are just creative claims out of whole cloth that are obviously without merit and that they are just stalling.”

In a verbose and commanding, yet empathetic way, Goethals reminds Paul that he knows exactly how long it’s been since the shooting — two years and four months — and that it will be worse for him if Dekraai’s conviction is one day overturned because Goethals didn’t methodically deal with this new evidence.

“These are not fabricated claims. … If I don’t do what the law requires me to do, any short-term satisfaction that you get, I don’t think is going to be very long-lasting.”

Paul goes home. He sits by the bay windows where he last saw Christy alive. The chair next to him is empty. Instead of sharing a cup of coffee with her, he sips whiskey alone. He talks to the walls, praying she can hear him.

“The kids are doing ok,” he tells her. “But, this has turned into such a mess, Christy. Such a circus.”

He tries to convince himself to understand Goethals, but he cannot. His anger and his pain are overwhelming. Whatever this other stuff is, it all still means that justice for Christy — and everyone else — is delayed.

“It just doesn’t make any sense. The guy admitted it.”

“Why are we still here?” he asks aloud, staring into the bright white light of the moon. “Why?”

Paul Wilson talks about his frustrations with the case of accused killer Scott Dekraai during a recess in the motion hearing underway in Orange County Superior Court on March 18, 2014 in Santa Ana, California. Credit: Mark Boster-Pool/Getty Images

The halls of the courthouse are thick with adrenaline and the buzz of fresh new fodder. Even for Southern California, you can tell, this is going to be a show.

For Dekraai’s case, hearings on what the media has now dubbed “The Snitch Scandal” are arguably bigger than the upcoming trial for his murders. And, for Scott Sanders, this is the single most important courtroom moment of his career.

He and Cathy have now completely taken over a conference room in the office. Colleagues still snicker about him, but they’re also coming around to understanding the impact of what he’s uncovering. He’s set to call more than two dozen different prosecutors to the stand, along with sheriff’s deputies, police investigators and inmates. This is now much, much bigger than just Dekraai and Wozniak. This has the potential to upend decades of cases that have ended with convictions.

Gang violence, domestic crimes, rapes, robberies, murders. The prison cell doors could swing open, unleashing the nightmares Orange County thought were locked away for good.

Everyone in the courthouse cares. Everyone is watching.

As Goethals drapes his black robe over his suit, he feels that weight, too. His courtroom — the largest one in the county — is packed, wall to wall, with interested onlookers.

Judge Thomas Goethals listens to arguements during a motion hearing in the trial of Scott Dekraai , who is accused of killing eight people in a Seal Beach beauty salon, on March 18, 2014 in Santa Ana, California.Credit: by Mark Boster-Pool/Getty Images

Goethals takes a deep breath, opens the door and walks to his seat on the bench. The room exhales and stills.

It’s the start of four months of testimony on the scandal, and it’s just as theatrical as everyone predicted it might be.

Goethals: Mr. Sanders, would you like to call your first witness?

Scott stands in his place behind the defense table and publicly reveals, for the first time, the name of the snitch at the center of it all.

Scott Sanders: Yes, Your Honor. At this time we'd call Fernando Perez.

Fernando appears and walks to the witness stand. Scott isn’t quite sure where he came from. He assumes protected custody. The bailiff asks him to raise his right hand and repeat after the clerk, who reads:

Clerk: Do you solemnly state that the evidence you are about to give in the case now pending before this court shall be the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, so help you God?

Fernando Perez: Yes.

Scott and Fernando begin a bickering exchange that will go on in the courtroom for three days.

Scott is relentless, circling back, unwilling to accept easy answers. In a courtroom filled with prosecutors and police officers trained to project control, Sanders brings something different: the quiet menace of endurance.

And it pays off. While Fernando starts out smug and cocky, it becomes clear that he’s been highly coached. His defiance exposes cracks and lies, even if he never quite gives Scott the answers he wants.

Scott: You weren’t looking out for these people. You were trying to collect —

Fernando: I never asked them — I never asked them any information. Not at all.

Scott: They all just spilled their guts to you?

Fernando: Basically.

…

Scott: Do you remember writing in a note, “Garcia, it would be a good idea to move Downer here and to move Downer and to move Eddie Boy in for a minute so I could work these dudes.”

Fernando: I don’t recall too much of that.

…

Scott: You’re asking questions. In the back of your mind —“I’m an informant, I need to get valuable information.” You’re thinking about that?

Fernando: I’m just jotting everything down.

Scott: Are you, when you’re an informant —

Fernando: Right.

Scott: — talking to Mexican Mafia members, thinking, “I’ll ask questions that are important and I hope to get important information back”?

Fernando: Yeah, I guess you can say that.

Fernando’s testimony is certainly interesting, but Paul isn’t seeing the seriousness that Goethals has been describing. All he can think is, what the fuck is all this for? What a waste of time. So, he got people to confess to something we know they did? Who cares?!

During a meeting, he asks Wagner, point-blank, in front of the other two dozen family members.

“Is this stuff true?”

Wagner looks at Paul. The severity of his icy gray eyes stare back into Paul’s softer brown ones.

“It’s all a lie,” Wagner tells him. “Scott started this whole thing, and none of it is true.”

Monday, March 24, 2014 was supposed to be Scott Dekraai’s trial date — the day he would finally stand before a court of law and face the fair trial guaranteed to every defendant by the U.S. Constitution.

Instead, prosecutors, defense investigators, victims, witnesses and press gather before Goethals for a different reason. It is only three days into the evidentiary hearings on the snitch scandal. Only one witness has testified so far. Goethals tells the lawyers for both sides that he’s going to push the trial to June 9.

Paul has had enough.

“The coward sitting next to Mr. Sanders has taken Christy from me. And as this continues, each time I have to look at him and his defense, I ask myself how they can live with dignity and integrity.”

Scott, as he always does, swivels in his chair from behind the defense bar and looks directly at Paul as he addresses the court. The attention, the eye contact — Scott believes Paul deserves that, even when the attacks are personal. And today, they are very, very personal.

“Being a husband and a father myself, I could never look my family in the face and do what you do, Mr. Sanders. Shame on you, Mr. Sanders. Shame on you. As far as I’m concerned, you stand in the same shoes as that coward sitting next to you.”

Laura Webb’s sister Bethany speaks, too. So does David Caouette’s son, Paul, and Michelle Fournier’s brother, Butch.

But no one cuts like Paul.

Scott is a bleeding heart. He has tremendous empathy. A part of him wonders if he’s doing the right thing. What if I’m wrong about all of this?

Fear creeps in for a moment, but then …

No.

The emotion quickly fades.

Scott has always believed, wholeheartedly, in the causes he takes on. To Scott, crimes are manifestations of complicated and painful existences. He realizes that this is an easy position to take, as someone who has never lost someone to a violent crime, but he never wavers for more than a few fleeting moments about his duty.

And taking it face-to-face from Paul, well, that pain must be pretty minimal compared to the pain of everyone else in the room.

And so, the hearing continues. And it drags on long past the June 9 trial date.

Paul has no choice but to endure it. He’s promised Christy he’d be there and now he’s trapped — captive, imprisoned, forced to listen to each and every fragment of evidence, no matter how small. But being forced to sit there means that Paul is listening.

He hears Ben Garcia insist that it would be impossible to arrange for certain defendants to be housed next to known informants. He hears prosecutors deny any kind of snitch database.

But he also hears an informant named Oscar Moriel brag on the stand that he’d go “hunting,” driving the streets of Santa Ana with a 40-caliber Smith & Wesson.

“Just started shooting,” he testifies. “Hit a few people. Just took off.”

And then Paul hears recordings of Garcia and other sheriff’s deputies incentivizing Moriel. When Moriel says his memory is faded but might return, with the right kind of help, they tell Moriel that he could start his life over in the U.S. Army. A life of government-sanctioned killing.

Bill Grover: You want to legally kill some people, huh?

Moriel: Yeah, I want to go fight. If that's possible, I want to go.

Scott looks back at Paul as the tapes play. He sees his back pull up.

Charles Flynn: It's much nicer when Uncle Sam's behind you on it.

Moriel: That's what I figured.

Flynn: Then you know you get away with it.

Moriel: That's cool.

Flynn: If you want to go over there and shoot, actually, the quickest way is probably the Army. … You go in like in the Rangers and they're going to go, ‘Hey, man, going over next week and they're short 200 guys. Anybody want to go?’ And you put your fucking hand up and bam, you're on the way.

Paul also starts to see a side of the prosecution that isn’t so pure. During a break, when Goethals is gone from the courtroom, one of them begins putting on a little show for spectators by walking around, lifting up chairs and mocking Scott Sanders as a crazy person who invented the idea of missing evidence.

“I wonder what’s hiding under here?” they say, as Garcia and others bellow with laughter.

“What a nut,” someone says about Scott. “He just sees conspiracies everywhere.”

A month ago, Paul would wholeheartedly agree. But he’s starting to wonder if perhaps he was naive to believe that the good guys are always on his side of the courtroom.

Part IV

There was a minibike in a garage. That’s how it all started.

Well, actually, it started because he had a shitty dad, but it’s easier to start with the minibike.

Mark Cleveland and his buddy wheel it out under the Southern California sky and into the field next to the garage they lifted it from. It is March 11, 1972, Mark’s 18th birthday — the day the law says he becomes a man.

Mark knows he’s meant to be a good guy. His dad is a cop, after all. But it is confusing because his dad also uses his police belt to whoop Mark.

Riding the mini bike in circles in that field gives him a momentary mental break from that reality. For a while, he isn’t thinking about anything else.

Then the lights flash, the handcuffs click, the door of the Orange County Jail cell thunders shut.

Mark Scott Cleveland, son of a California Highway Patrol sergeant, is now more than just an adult. He is a criminal.

Mark Cleveland and his grandparents in 1971. Credit: Cleveland family

It doesn’t take long for Mark to figure out how things work on this side of the law. For one, he is tanked with the worst of the worst, sent to protective custody because, as one guard put it, “your dad would have us killed if anything happened to you in here.”

A deputy arrives. He’s mingling with the inmates. Mark asks him what’s in his little notebook.

“You know, I could help you out and maybe we can get you outta here early,” he says. “There are a lot of things we can do if you have information.”

Information? Mark is skeptical. Another inmate reassures him.

“You’re in here, you’re already labeled. You’re a snitch whether you like it or not. So you might as well figure out how to do it.”

That first arrest isn’t a very big deal. Mark gets out quickly anyway.

But that feeling he got, circling the field in that stolen minibike? Now he’s chasing it. And he figures out a less conspicuous way to escape.

He’s noticed that when his mom comes home from her job as a nurse, she pops a pill that turns her into the nicest, sweetest person.

He tells his younger brother, “Those pills really make her happy.”

So Mark starts taking them, too. And, of course, mom catches on.

She hides them. He finds them.

She hides them. He finds them.

And then, one day, he realizes he can just get them on the street instead.

So begins a long cycle. One that would stretch on for decades. It goes like this: Mark gets high. Mark does something illegal. Mark gets caught. Mark goes to jail and then Mark gets out. Mark gets the attention he’s been craving from his dad.

Mark Cleveland and his mom. Unknown year. Credit: Cleveland family.

But as the arrests pile up, the jail stays become longer. Detoxing behind bars really sucks. Mark is desperate to get out quickly. The words replay in his head:

Maybe we can get you outta here early.

You’re a snitch whether you like it or not.

Mark is at a great advantage. He’s in for minor stuff, but his status in protective custody means he’s housed with the baddest, most high-profile criminals.

It works so well.

A homicide prosecutor in the District Attorney’s office notices that Mark’s info is pretty darn good. What he’s handing over is leading to quick guilty pleas.

“The defense attorneys see it and they just throw in the towel and make a deal,” he tells Mark.

Suddenly, Mark’s got privileges. They make him the clean-up guy — the inmate who goes from cell to cell with a mop, fresh toilet paper, stuff like that.

His blue armband, indicating that he’s in protected custody but not dangerous (that would be yellow or red) gives him freedoms like phone use. He can easily call his handlers.

Mark figures out that this all actually works best if he’s not the only one gathering info. So he levels up. He starts proudly wearing his snitch status.

“You got info? You wanna get out?” he tells guys, as he mops their cells. “I got a line straight to freedom.”

That line to freedom? It’s getting more and more direct.

Mark jots down names and inmate numbers, the gist of the confessions, and goes to the phone in the day room.

Ring.

He confidently holds the receiver to his ear. His angular features give his face

Ring.

He feels good about himself. He’s doing the right thing. Catching bad guys. Just like his dad would have wanted.

“Hey Tony, it’s Mark Cleveland. I got some new stuff for ya.”

Mark doesn’t know it yet. Right now, he just thinks he’s talking to some line prosecutor. In reality, he’s feeding the career of the man who will quickly rise through the ranks, first in the DA’s office, then by becoming a judge, and eventually the elected District Attorney.

The man in charge when the snitch scandal begins to unravel.

Tony Rackaukas.

As Mark recalls, the conversations would go like this:

“I read your statement. Fantastic.”

“I was gonna have to go to trial on that, Mark. I'm not gonna have to do that now.”

“I'll note that you called and gave us this, so you can get credit.”

So Mark levels up again. On his daily rounds, he not only distributes toilet paper, but also newspapers.

Newspapers are full of information about recent high-profile cases.

A few hours later, he goes around again to pick them back up. Suddenly, his fellow inmates have a lot to say.

“Mark, Mark,”

His name echoes through the tank.

“Hey, I got something on this guy.”

“Can you get somebody to come down and see me?”

“You know, I want to get the hell outta here.”

“I really appreciate it, man. You’re the best, Mark.”

Mark starts carrying around a briefcase. Inside, he has notes with everyone’s info — newspaper clippings, inmate numbers, and prosecutors’ direct desk lines.

“They take my calls because they know my relationship with Tony,” Mark tells people.

Tony, according to Mark, is leveling up, too.

“So he went from a, you know, regular, just, a plain old everyday DA, to homicide DA,” Mark recalls years later, sitting at his kitchen table with the contents of that old jailhouse briefcase. “But after the relationship begins with us, this guy is just unbelievable. He is getting convictions without even going to trial. He's, you know, he gets promoted to head of homicide and he says to me …

“Mark, it's because of you and the numerous cases you give me, that's allowing me to get these convictions.”

In the 1980s, the Orange County District Attorney's Office is a proving ground.

Young deputies, like Tony Rackaukas are fighting their way up through burglary and drug cases until they earn a place in homicide. It’s an atmosphere of competitive camaraderie.

Tom Goethals runs the unit. And every Thursday morning at 7 a.m. — before hearings and trials reconvene — he brings the team in to discuss case strategies, and decide which murders should be filed as capital cases. The meetings are spirited and blunt. But to Goethals, they are essential.

Goethals is a measured, even-handed prosecutor. He has a deep admiration for Abraham Lincoln. He quotes his writings and builds his ideas of fairness and justice off the former President’s example. He is humble, but proud of his career. His photographic memory makes him an excellent litigator. Although one of his favorite stories to tell has nothing to do with the law at all. It’s about how his relative designed the Goethals Bridge, connecting Staten Island to New Jersey, and how New Yorkers often mispronounce it.

Tony Rackaukas, by contrast, has a harder edge. Born in East Los Angeles in 1943, he had a modest childhood, enlisted in the Army after high school, and served as a paratrooper in the 101st Airborne Division before putting himself through law school.

His colleagues start calling him “Rock,” and his physical demeanor matches the nickname. He’s formidable, and not just in court.

Goethals ties his shoelaces and looks up.

“Do you wanna run the loop?” Goethals asks his colleagues?

A few years ago, when he first heard about a little-known janitorial locker room in the courthouse basement, he’d sneak down for a solo run at the lunch hour. But little by little, it’s grown. Nearly 20 people are jogging up and out the ramp from the security room in the garage. Chatter from his Thursday morning meetings spills over as they traverse a six-mile loop around Santa Ana.

“Runners’ privilege,” they like to say. “What happens on the run, stays on the run.”

People start to notice a pattern. Rock has an uncanny ability to make cases through informants. The frequency doesn’t cause concern as much as intrigue.

“I’ve got an informant on that case.”

“I have another informant.”

How does that keep happening? That’s pretty amazing fortune.

Snitches were already scandalous in the 80s.

In fact, in neighboring Los Angeles County, they were making big news. Prosecutors and deputies had just been caught planting informants next to targeted inmates to elicit confessions in Men’s Central Jail. And sometimes, deputies would circulate press clippings about ongoing cases so that snitches could “study up.”

Sound familiar?

It’s the same scam that Mark Cleveland was running in the Orange County jail.

In June of 1985, an LA Times reporter wrote about the rise in informant use in Orange County.

“In the last five years, jail informants have testified in more than a hundred major Orange County cases,” the article says. “Jail inmates call them “snitches.”

The main prosecutor quoted in the story is Tony Rackaukas. He’s mentioned eight times.

“Ideally, all my witnesses would be bishops and nuns,” then-deputy Rackauckas says, defending the practice. “But that's not the real world.”

Four years later, the LA Times digs deeper. A reporter shows up to the Orange County jail and requests a media visit with an informant who has a reputation for telling it like it is.

It’s Mark Scott Cleveland, and he agrees. According to Mark, he tells his entire story, revealing the betrayals that are happening in the snitch tank in Orange County.

The interview goes on for hours. But when the story comes out, the focus is almost entirely on the misconduct in neighboring Los Angeles County. Mark’s part is reduced down to one line. He’s described as a “veteran informant,” who tells the reporter that truth doesn’t matter. “A way you can get around maybe not being able to get a confession right away is create one,” the story quotes him saying.

Mark remembers prosecutors gave him the cold shoulder for a bit, but nothing else comes of it.

By the late 90s, Rock sees an opening.

District Attorney Mike Capizzi announces he’s stepping down. The office is eager for a new leader. Goethals himself considers running, but instead commits to helping his close friend Brian Brown mount a campaign. He even imagines himself serving as Brown’s campaign manager and, if things go well, his chief deputy.

Rock, who by now is a sitting judge, is an obvious potential opponent. So, Goethals goes to see him in his chambers to ask about rumors that he’s running, too. But Rock is coy about it. Non-committal.

Only later does Goethals learn that Rackauckas already had his campaign organization built.

Brown has no choice but to drop out. “Rock’s got all of the assembly districts locked up,” Brown tells Goethals. “He’s done all the political legwork. We can’t beat him.”

To Goethals, the maneuver underscores Rock’s ambition, but it doesn’t stop him from supporting his colleague. Goethals hopes Rackaukas will end up bringing positive changes to the office. In fact, he introduces him at his first major fundraiser at the Revere House in Santa Ana.

“He’s going to breathe fresh air into the District Attorney’s Office,” he tells the crowd.

Less than 12 months later — although it wouldn’t come out publicly for 19 years — the state’s chief assistant attorney general sends a letter to Rackaukas, warning about potential misconduct in the way they use informants. Rackaukas claims he fired a prosecutor in response, but quietly, his office continues to expand the use of jailhouse informants.

It’s 2000 and the law is finally catching up with Mark Cleveland.

He’s been picked up for a DUI hit-and-run where three people were hurt. His attorney pulls him aside in the courthouse corridors.

“They’re waiting for you,” he says. “They found out about all your burglaries. The judge is going to revoke bail, put you on a million-dollar bond, and hit you with three strikes. Twenty-five to life. You’re through.”

The words land like a final judgement. Mark asks his lawyer: “Can you stall for me for just 10 minutes?”

He bolts.

He runs from the courthouse to his car, makes a very quick stop at home — where he hurriedly tells his housemates to “stay until they kick you out” — grabs a few papers, and heads for the California-Mexico border.

He disappears into the mountains for a while. A friend lets him crash at a ranch outside Guerrero, far from the cities. He buys a used limousine in Tijuana. The villagers stare when he rolls through town in a black, shiny anomaly among the dirt roads and one-story homes. Locals think a cartel boss has arrived. For nearly a year, he hides out by sticking out.

But Mark is restless. He returns to Tijuana to reinvent himself. He buys more limos, rents a four-bedroom house, hires three young women and one young man, and builds a brothel.

Business is constant. Mark takes half of everything.

Mark Cleveland, unknown year. Credit: Cleveland family.

The cars are driving every night, too, ferrying American tourists from the Zona Norte down to the clubs. To hide all his illicit cash, he makes sure to book some legitimate business — mostly weddings and quinceañeras. But most of the time, he’s driving for crooked federales and cartel affiliates. He never asks questions.

Mark Cleveland is finally somebody.

Years go by. Nearly eight of them pass while he’s living life on the lam.

One afternoon, he’s driving a limo to the bank to make a large deposit. He notices el policia federal. Then another. And another. Suddenly, he’s surrounded, rifles are raised, they’re ordering him out. It doesn’t quite hit him until he’s sitting at headquarters watching them count nearly $10,000 cash on the table.

He isn’t just in trouble in Mexico. He’s about to get deported.

Riding back up across the border, Mark is in a police wagon with a couple accused of a crime that’s splashing across local headlines. By now, Mark knows what to do. He befriends them. He gets them to talk.

By the time he arrives back in Southern California, he’s already got a plan for wiggling out of his four strikes — what would otherwise be an automatic sentence of 50 years to life.

Well, the plan doesn’t go exactly how he thinks it will.

The couple in his transport van is wanted in San Francisco, and prosecutors there scrutinize Mark’s story, and ultimately don’t use him.

Then he snitches on a case back in the Orange County jail and finds out that it isn’t so cool to be labeled an informant in the tank anymore. A guy pulls him through the bars and screams, “you fucking snitch. I’m going to fucking kill you.” The folders Mark is carrying back from court drop to the floor. He suffers a head and neck injury that he says takes a year to heal and leaves a nasty scar.

Years later, Mark sits on the couch in his trailer in Garden Grove. The static of the freeway dulls his raspy voice. His bright blue eyes are a striking contrast to his long black hair and thick mustache.

His lawyer listens empathetically as he goes on about how he got here.

“You know who you should talk to?” his lawyer interrupts. “There’s a guy in my office named Scott Sanders. He’s digging on this whole informant thing. I think you could be very valuable to him.”

He gives him Scott’s number.

Mark calls.

Scott is highly skeptical, of course. He’s just spent the better part of two years trashing the credibility of informants. He wonders what it might look like to rely on one.

But Mark sounds confident, convincing, even if his information is quite shocking. Unlike Fernandez and Moriel, Mark doesn’t try to pretend it was all above board. He is seemingly unafraid to tell it like it is. Mark tells Scott about the phone calls with Rackaukas, about handing out the newspapers. He tells him exactly how he managed to get out of two 25-to-life sentences.

Scott knows that he cannot just take Mark’s word for it. For what it’s worth, I had the same feeling the first time I talked to Mark. Both of us went to Mark’s home and sifted through his briefcase of documents he’s kept over the years. Some of them have now been digitized by an attorney, but many are loose pieces of worn college-lined draft paper. The kind they hand out in jail. He also has nmate numbers, prosecutor’s direct desk lines, even clippings from the Register.

And Mark has documentation for almost everything he alleges.

His handwritten notes show how he did it:

“...he grabbed the kitchen knife and walked towards his wife.”

“He told her not to get scared and not to let police trick you into admitting anything…

“...discussing the details and payment for his girlfriend’s murder…”

Mark — now with long, thick black hair and a full mustache — slips back into the role he had perfected decades earlier. Back into the cycle he knows better than anyone.

“I’ll say, ‘the devil is in her, and she wants to kill you.’ Do you think that sounds good, Mark? … I told him it sounded like a good strategy to beat his case.”

“He told me he wanted the fucking bitch dead. He said his only regret is that he failed to kill the bitch.”

“Sparky said there are also some witnesses that live in the neighborhood but none of them saw his face because he wore a black sweater with a hood pulled over his head.”

He starts building cases, one by one. His briefcase records show statements on 13 defendants. Mark remembers it adding up to 8 cases. Letters he kept, written by his now-deceased attorney to the court, corroborate that he was a cooperator in at least seven.

Some were murders, others serious felonies. By the end of it, Mark is one of the DA’s most productive informants.

His transfer records show that in about four years at the county jail — with his sentencing continuously being delayed — he’s transferred 89 times to new locations.

According to Mark, it’s deliberate. They’re putting him near the guys they need statements from.

Mark Cleveland sits with his briefcase of documents and snitch notes. Credit: Sara Ganim

A sampling of Mark Cleveland's snitch notes. Credit: Sara Ganim

Mark Cleveland isn’t sure what will be considered enough.

It’s never laid out explicitly.

He just keeps working — just like he always has.

One day, he’s brought to the courthouse for a status hearing. It feels routine. He’s waiting in the holding cell next to the judge’s chambers while his attorney meets with the assistant district attorney on his case.

When it’s over, his attorney comes in and sits with him. According to Mark, these are pieces of what is said:

“Several district attorneys from cases you worked on were there. They all spoke highly of you.”

“They all agreed you deserve to be free.”

“I’m going to try to get you out today.”

Whatever was said, court records show that Mark’s two three-strikes cases are dismissed that day. So are almost all of his charges, except for one count of DUI with injury. He’s given time served, and he does, in fact, get out that day.

Mark never steps foot in a state prison. He never stands before his victims. He simply cooperates. Mark gives Orange County prosecutors convictions; they give him his life back.

In 2015, Tony Rackaukas is asked about Mark Cleveland during a lengthy interview with ABC7, and he denies knowing him.

Producer: Mark Cleveland is another longtime informant who I think you're probably familiar with.

Rackaukas: Can't think, the name's not familiar.

Producer: He has been a problem informant, according to your informant index file. He was also quoted in the LA Times years ago, talking about how ‘if you can't get a confession you just fake it,’ and yet he's been used by your office as an informant as recently as 2011.

(Off-camera assistant): Was that name on the list, because we asked you — it was? Ok.

Rackaukas: Mark Peterson? I don't know. I'm not, I'm not familiar with that.

Producer: Mark Cleveland.

Rackaukas: Oh, Mark, I'm sorry, Cleveland. Uh, I, I'm just, that's not, I'm not recalling that.

Two years later, when interviewed by 60 Minutes, Rackaukas admits to using Mark as an informant, but attacks his credibility.

Correspondent: Mark Cleveland, do you know who he is? Does that ring a bell?

Rackaukas: I do know who he is. I remember him having been an informant many years ago in a case or two, but my memory on that actually is not that clear.

Correspondent: How should we take Mr. Cleveland’s statements that he made to us about all of this?

Rackaukas: I think you should assume you are talking to an informant, and if he’s talking, then he’s probably lying.

Correspondent: But this idea that he was part of this informant program and that he could just pick up the phone whenever he wanted and call the District Attorney’s Office.

Rackaukas: Fantasy.

Rackaukas did not respond to multiple requests to participate in this story.

Tony Rackaukas talking to ABC7 in 2015. Credit: ABC7/Youtube

It’s the first Monday of August 2014 — just days after the hearings wrapped up — and Judge Tom Goethals has called everyone to the courtroom to announce his decision.

The court clerk hands out copies to the lawyers. Behind the bar, the usual packed gallery sits anxiously. Scott can sense their presence but he’s focused on the papers before him.

He immediately flips the opinion to the last page. There’s static under his skin, a metallic taste in his mouth. It’s adrenaline. His fingers race to the last line:

Motion denied.

His throat closes. Stomach tightens. It feels like a wave of icy cold dread has just crashed on top of him. This isn’t just a setback for the case. It’s also a reminder. If Scott is wrong about all this stuff, it’s going to have major consequences for the public defender’s office. And for him. He will likely face a ton of public ridicule. Not to mention, the wrath of the families of the innocent people who were brutally slain.

Goethals' ruling does acknowledge misconduct. “Current and former prosecutors, as well as current and former sworn peace officers,” he writes, “perhaps suffered from a failure of recollection. Others undoubtedly lied.”

But he calls it negligent, not malicious.

Essentially, his ruling boils down to this:

Yes, they lied.

No, it wasn’t bad enough to take the prosecutors or the death penalty off the table.

But, it was bad enough that it violated Dekraai’s rights and the jailhouse recordings will remain secret.

Scott reads and re-reads the opinion over and over that day, with different emotions each time.

Relief: At least Goethals wasn’t intellectually dishonest about what was said in court. Deference to prosecutors is a real problem, and he didn’t give them a free pass.

Disappointment: But then again, he wasn’t courageous.

Anger: They’re celebrating. They think they won. That’s fucked.

Another lawyer might call it quits, even give himself a kind of victory for exposing more about the snitch operations in Orange County than had ever been public before. Someone else might shrug and say they tried.

But not Scott Sanders. He reads it again with a new emotion.

Resolve: They think it’s over. It’s not over.

That’s because Scott has an incredible chance at a do-over. He isn’t just working within the confines of the Dekraai case. He also has Wozniak. Just as the Wozniak case helped him figure out the real identity of Inmate F, the Wozniak case could also give him another shot at exposing all of this. He essentially gets two attempts — in front of two different judges — to get everything he’s seeking.

Scott goes back to Mark Cleveland.

Mark has always wanted a starring role in a big story. He’s about to get it.

“Is there any chance that the special handling deputies weren’t keeping notes on the snitches?” Scott asks.

“That’s the biggest bullshit ever,” Mark replies.

Scott knows he has to get his hands on those records. He finds himself sitting on the floor of an appellate lawyer’s office, sifting through Mark’s case files when he gets a clue: Notes on Mark’s snitch work. They call it an “informant index.”

This one couldn’t be more clear about Mark’s credibility.

In bold, underlined capital letters it reads: PROBLEM INFORMANT. Below it, there’s a narrative written by a cop in Anaheim who tried to use Mark in an undercover sting. Instead, he caught Mark planting evidence and stealing cash from someone’s house.

It’s a note made 30 years earlier, in 1982.

This should have immediately ended his informant career, Scott thinks.

But he knows that it didn’t.

And worse, Scott sees that law enforcement’s knowledge of Mark’s lying problem was repeatedly hidden from the defense teams in the cases he was working on.

They knew he was lying, but they kept secretly using him.

So, Scott goes back to the overnight shift at diners and parking lots. Except this time, it’s the holidays and he ends up in Ecuador, sipping cafe con leche on uncomfortable metal chairs in the mountains near Quito. He’s supposed to be on a family vacation.

His wife doesn’t give him a hard time this go-around.

“Do whatever you need to do,” she says, as she and the kids head out. “We’re fine. We’re having fun.”

She looks at Scott, who is balancing his laptop on his knees, and nods in approval.

Scott Sanders in Ecuador, writing a 752-page motion in the Wozniak case. Credit: Priscilla Sanders

It’s the kind of encouragement Scott needs. He starts working on a new filing — one that will top his previous personal best. If the court community was shocked by the 505-pager in Dekraai, they’d only be left to laugh at the size of the Wozniak motion. It will end up being a whopping 752 pages, with 25,000 more pages of exhibits, and no doubt one of the largest court filings of the modern era.

This story is already about extremes. Why not break some more records?

Scott uses Mark Cleveland to show how entrenched and problematic the Orange County informant network has become. The motion describes him as a classic example of a compromised snitch — trading information for freedom rather than out of civic duty.

He alleges three decades of systemic abuse.

And it’s more than just Mark.

Just a few weeks ago, he got more boxes of discovery delivered to the office. And unbeknownst to anyone else — yet — the contents are about to detonate the black box that has been concealing the truth of the scandal for decades.

This story draws on first-person interviews with those directly involved whenever possible, and relies on official records where interviews were not available. In a few instances, scenes were created based on reporting with people who were knowledgeable about interactions with people who could not be interviewed.

Switchboard researcher Lilly Bartilucci contributed to this story.

Sara Ganim is an award-winning multi-platform reporter. She started her career in local news, won a Pulitzer Prize, and is now a reformed cable news gal who works mostly in long-form audio and print. Her latest podcast, Believable: The Coco Berthmann Story was named one of the best podcasts of 2023 by The Atlantic. She lives in New York with her TV-lawyer husband and two young daughters.