Poison in the Well

By Sam Norton

Dropped in the middle of endless cornfields along a straight, desolate country road in southwest Ohio, Crosby Elementary School stands in near-isolation.

On a frigid night in late January 1985, its light stone facade looms larger than ever over its surroundings. That night, a sharp winter wind whips across the region, but the 500 people packed into the Crosby gymnasium hardly feel it. Their attention is fixed on something else — something that will consume the town for decades to come.

Six men sit at a long grey folding table in front of the crowd. Their tailored blue suits and corporate demeanor clash with the attire of those in the audience: mostly hard-working country folk. It’s a packed gym and many are forced to stand, waiting apprehensively for these well-dressed visitors to finally speak. Of the hundreds of people gathered, most are from nearby Ross, Ohio. But scattered among them are some outsiders, too. There are anti-nuclear activists. Journalists. Even Ohio Congressman Tom Luken has made the trip.

These clean-cut corporate types aren’t locals, but they do represent something that has defined Ross for decades. They are all associated with the Fernald Feed Materials Production Center, a sprawling government facility built in the 1950s that engulfs over a thousand acres of land just a few miles north of the school. They’re employees of the agency that built and owns Fernald, the Department of Energy (DOE), and the private contractors that currently run operations, National Lead of Ohio (NLO).

Their cold, disinterested eyes stare blankly into the crowd. Pale faces, deeply lined with age, are set in practiced stoicism, hardened by years of indoctrination into the supposed nobility of their work: preserving America’s nuclear might through facilities like Fernald.

For the past 30 years, the residents of Ross have known very little about the facility, other than that it was government-owned and might be nuclear. This was on purpose. The DOE kept the plant a tight secret to hide that the Fernald facility was processing and assembling the cores of nuclear warheads.

But recently, information started to leak out. The Cincinnati Enquirer ran a front-page story a few weeks earlier, exclaiming, “NLO Checking Possible Uranium Leak.” The article revealed how uranium, the radioactive metal that Fernald purified and assembled into the fuel cores of nuclear weapons, had been detected on three off-site drinking wells in Ross.

The article sparked community outrage. This town-hall-like meeting at Crosby Elementary is a response to that.

The DOE and NLO representatives eventually begin speaking, offering flat, rehearsed explanations to mothers and fathers who are terrified that their children are slowly being poisoned from inside their own homes.

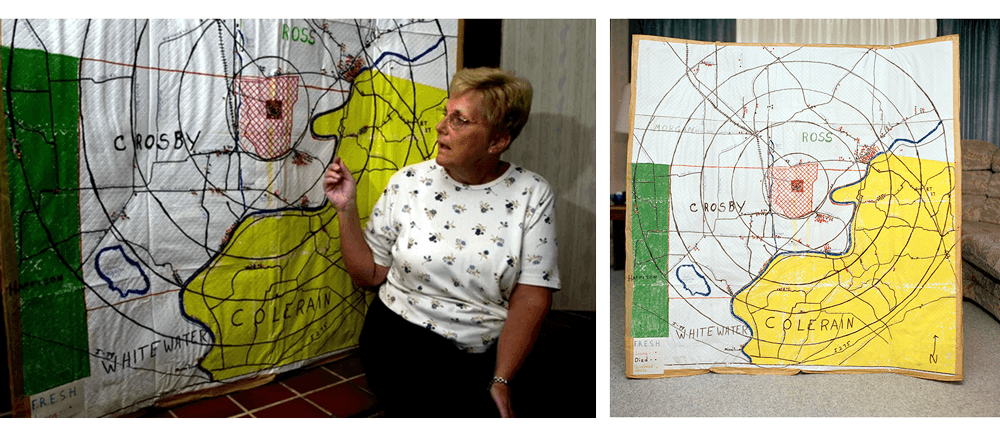

One of the suits stands up. He walks to a rectangular sign propped up on a wooden axle next to the table, which had been hidden under a blanket while the townsfolk filed in. Dramatically, he tears off the cover to reveal a map of the town. And then he points to three contaminated wells.

At first, sighs of relief echo through the gym. Many people see immediately that their wells are safe, according to the map. But in the back of the room, Lisa and Ken Crawford sit quietly. Before the meeting, their landlord had warned them that their well might have been contaminated by uranium. Stout and in her early 30s, Lisa has wispy, light-brown hair cut short into a pixie bob. Her sharp brown eyes stare blankly at the map.

Lisa and Ken Crawford in their living room, circa 2006. Credit: The Cincinatti Enquirer/Craig Ruttle.

This confirms what her landlord feared.

The Crawfords have lived in Ross for nearly five years with their young boy, Kenny. They are a small, tight-knit family who found a home in the small, tight-knit community of Ross. The dream of raising their son in a quiet, rural existence seemed a pleasant reality until their landlord came knocking.

As the volume in the gym rises, Lisa and Ken’s stony faces remain taught. The meeting carries on for over an hour, as relieved but still angry Ross residents pepper the six representatives with questions. Over and over, the men reiterate that the contamination is “fine” and that very little uranium is actually escaping from the Fernald plant. They’re so confident the drinking water is safe to consume, in fact, that NLO had even sent the Crawfords a letter stating so.

Lisa’s round face rests sternly. She’s been waiting patiently for her turn to speak, and as the meeting draws to a close, she’s finally called to the front. As she marches toward the table in her bright pink sweatshirt, a blazing fury swirls around her head. Their suits can go to hell, she thinks. Their shallow words and map can go to hell, too. She has a 6-year-old at home. These men are damn-well going to prove that the water is safe for my child.

In one hand, she holds six red solo cups, the kind easily found at house parties at nearby universities. In her other hand, she carries a gallon of her own well water. Lisa steps right up to the folding table and slams the jug onto its surface. The men stare back. Her eyes bear into theirs as she opens her mouth.

“Your letter tells me that this water is safe to drink,” she says. “I want to see every one of you drink it.”

If there is any illusion that Fernald officials are in control of the narrative, it collapses in this moment. By dawn, the front pages deliver a verdict they cannot spin.

The solo cups are left untouched.

It’s a chilly fall afternoon in 1979, and Tom Carpenter turns onto Willey Road after driving for over half an hour through southern Ohio farmland. To his left, the scene is more of the same: large, muddy crop fields with dead corn stalks bending in the wind, and a few modest Midwest farmhouses dotted here and there. To his right lies his destination. In this landscape, it’s an entirely foreign sight.

Cows stand grazing in a grassy field in front of a chain-linked barbed wire fence, which stretches west for hundreds of yards along the narrow country road and north toward the nearby town of Ross. Tall deciduous woodlands partially obscure his view, but he can still make out the buildings behind the fence, factories and smokestacks poking over the treeline. A red-and-white checkerboard water tower rises clearly within its boundaries.

A photo of the outskirts of Fernald, the checkerboard tower rising above the trees, circa 1979. Credit: Tom Carpenter.

Tom keeps driving parallel to the fence, searching for something to indicate what this facility actually is. Just up the road, he finds what he’s looking for.

A small yellow sign on the fence reads: “U.S. Government. No Trespassing.” It also reveals the name of the facility, the Fernald Feed Materials Production Center. The cows munching grass outside the fence should have given credence to the agriculture-like label, but he isn’t convinced.

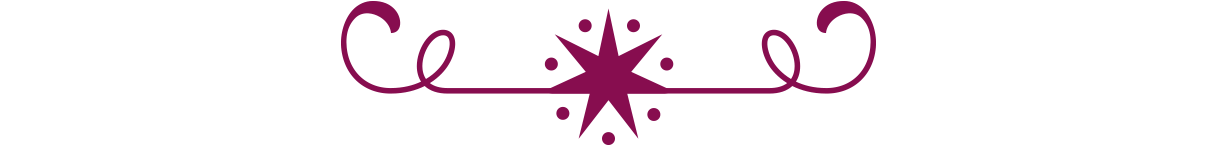

Tom is a tall, skinny man in his 20s. He sports shaggy dark hair, brown eyes, and oversized glasses that will soon fit right in with 80s fashion. He has a joyful face, despite the intensity of his work, and an excited, albeit fiery, way of speaking. His hands move in tandem with his passionate expressions.

Ask Tom about his thoughts on America’s nuclear weapons complex and he’ll begin in an even, almost understated tone. Give him a minute, though, and the energy shifts. His voice lifts, his thoughts hit a faster gear, and suddenly he’s speaking with full-throttle conviction. Still, he never loses his edge, and passion doesn’t overshadow his intelligence.

Tom’s gentle, almost nerdish exterior belies the depth of feeling and moral clarity that churn just beneath it. By the end of the decade, those emotions are starting to bubble up.

Tom Carpenter poses while being photographed for the Cincinnati Alliance for Responsible Energy, circa 1982. Photo by Mark Treitel/The Cincinnati Enquirer.

Tom is what you’d call an avid opposer of the rapid and unregulated growth of America’s nuclear weapons complex. He recently co-founded the Cincinnati Alliance for Responsible Energy (CARE) group and is in the midst of fighting the nearby Zimmer Nuclear Plant. Just a few weeks earlier, the Cincinnati Enquirer reported that a government facility in Ross was to be expanded.

Weary of the secret government programs that were already being uncovered in southwest Ohio, the news of a facility expansion in the area piqued his interest.

But no one at CARE has heard of Fernald. Not even Tom, a Cincinnati native, knew of the place. The local library had done little to aid his search for information. So, sitting amid stacks of books and newspapers in the quiet building, he decided to head north and investigate himself.

Tom makes note of the little yellow sign and drives further up the road, past the gated entrance, where a bridge crosses a small creek named Paddy’s Run. It appears to run directly under the perimeter fence. He parks his car off the road next to the bridge, grabs a small container, and starts making his way through tall grass down the embankment.

He reaches the creek. He isn’t far from the facility. It's just over the other side of the bridge. Sturdy tree limbs arch over the thin rush of water, narrow enough that he could jump over it. The stream is greenish-brown with a gravelly bottom, and the water gurgles slowly past. Tom spent his childhood exploring streams like this, so as he kneels to retrieve a sample, he notices something is missing.

The creek is completely lifeless.

No minnows dart under the rocks, no frogs leap into the current as he trots past, and no snakes slither into the tall grass. Looking around the muddy edge and into the surrounding brush, it’s entirely still. The only sound comes from the water. Even the birds are silent. Unsure what to make of this, Tom scoops some creek water into the container and screws the lid on.

Suddenly, a sound. Not of nature, but still recognizable. Footsteps. Tom turns around and looks toward the bridge to find four men in head-to-toe military attire.

They’re pointing military-grade rifles directly at his chest.

His heart drops and his lungs freeze. Tom slowly stands and raises his arms.

“Look, I’m just taking samples from the creek,” he says, the container shaking in his hand.

“You’re trespassing,” grunts one of them.

“No, I’m not,” he says, gaining back some of his confidence. “The other side of the bridge is trespassing. I’m on the right side.”

“Well, you should leave,” another one says coldly.

“Fine, I’m leaving.”

He scrambles back up the embankment, and the guards stare as he makes his way back to his car. They never ask for the water sample that he clutches tightly to his chest.

It isn’t until he pulls shut his car door that he feels he can breathe again. As he drives away, he glances back at the fence and the trees hiding whatever lies inside. Something that, as Tom had just been shown, is worth protecting.

What is this place? He wonders as he speeds south, back toward Cincinnati.

Fernald was born out of fear.

It was the 1950s, and the United States had just won World War II, but tensions with the Soviet Union were growing. If the U.S. wanted to maintain the nuclear strength that won the war for the Allies, it needed more uranium processing plants that could assemble nuclear warheads.

Fernald was chosen because it's flat, near a railroad and river, and accessible to skilled workers in the surrounding area.

Construction began in 1951 and within a few years, the factory was taking uranium ore mined from as far as the Belgian Congo, separating, purifying and forming it into tubes. From there, the uranium is sent to other facilities, where it is bombarded with neutrons, causing a chemical reaction that transforms it into plutonium. Plutonium is the radioactive element used in nuclear weapons to undergo fission.

The process of purifying that took place at Fernald created uranium waste sludge, plutonium, and uranium ash, and radioactive radon gas — all of which were stored in metal barrels and concrete silos on site.

National anxiety over the Red Scare meant that the DOE had little oversight of Fernald’s waste practices, and the process was carried out by contractors to create even more distance from accountability. For decades, no one dared cross their path.

By the early 60s, the height of the Cuban Missile Crisis, more than 3,000 people were employed by Fernald. Working here as a chemist, engineer, cook or janitor earned far better wages than most of the other jobs in the area. Fernald workers were sworn to secrecy, for fear of Soviet spies. But for nearly three decades, the plant ran well.

Or so it seemed.

Unbeknownst to the townspeople — even most workers — radioactive particles were billowing into the air, and seeping into the water.

By the time the community gathered in the school gymnasium to confront those officials in suits, over 500 tons of uranium and other hazardous chemicals had escaped from the plant’s ominous perimeter.

Lisa Crawford grasps my hand with both of hers, thanking me earnestly for my time, even though I was the one who desperately wanted the interview.

“We are simple folk,” she tells me, proudly.

When Lisa moved to Ross, she had no idea that, in just a few short years, her character traits would be put on display for the entire nation.

The family’s old white farmhouse on Willey Road — and just down the street from Fernald — has everything they could hope for: a garden in the front, a sandbox and plastic pool for her little boy, a well in the back, and a yard to play in. Ross is small, and the family formed friendships fast. Summers are filled with county fairs, and sunsets stretch over the vast horizon. In this small, picturesque slice of southwest Ohio, they truly felt at home.

There are rumors about the place with the armed guards on Willey Road. But workers at Fernald, who are often active members of the community, are instilled with a culture of secrecy. The town has accepted that. And so, when Lisa and her family moved there, they accept it as well. Lisa and Ken are preoccupied with their work and their family. They never wonder too deeply about the facility that billows smoke into the air and has trains barreling through it.

Lisa, like her neighbors, would have no reason to know that Tom Carpenter had driven right past her house that day he was chased away by men with guns drawn. She has no idea that since 1981, the DOE has known there is uranium in her well, and is hiding it from the public.

Tom Carpenter is sitting in his small Cincinnati apartment, surrounded by cardboard boxes. It’s two months after he encountered the guards outside of Fernald. Now, mounds of papers detailing the plant’s chemical releases surround him, scattered around his living room.

Immediately after arriving home from his visit to Fernald, he sent his water samples to a private laboratory in town. The results showed 15 microcuries per liter of uranium in the water. Today, accepted safety limits are set hundreds of times lower, but another realization unsettled Tom even more.

Uranium is almost 20 times denser than water, meaning many of the particles released into Paddy’s Run likely settled in the gravel bottom rather than remaining suspended in the water. Therefore, Tom knew the actual contamination was likely much higher.

This alarms him, so he sends his test results to the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency with a letter expressing concerns. Perhaps unsurprisingly, officials are uninterested. But Tom is not easily knocked off course. If they won’t ask questions, he will do it himself.

He hits Fernald with a public records request — under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) — demanding they hand over all information about their chemical releases into the air and water. FOIA legislation is only a few years at this point, but the newly minted federal law means the Department of Energy is forced to comply.

They send dozens of boxes, stuffed with papers and folders. At first, it feels overwhelming. But it’s hard to overwhelm Tom Carpenter.

He opens the first box. The smell is overpowering.

The papers are covered in Magic Marker. The DOE, relying on national security exemptions to the FOIA disclosure rules, has redacted almost everything Tom asked for.

But a smile creeps onto his face. These documents are carbon copies from typewriters. Typewriters leave an imprint. Rather than redacting and then printing, they’ve done the redactions last.

Tom gets an idea. He grabs a document from the floor and holds it up to the overhead light in his cramped apartment. He bursts into laughter.

He can see right through the Magic Marker. He can read everything that Fernald is trying to hide from him.

“That was the good stuff,” he recalls.

Tom spends the next several days working through the boxes and compiling all of the information. The documents reveal massive, unregulated chemical releases from the plant into the surrounding ground, water, and air. Tom can barely believe it, and he certainly cannot keep it to himself.

He sends out a press release and the response is swift. The DOE is furious, demanding to know how he got redacted information. He gleefully recounts their mistake, and they demand the papers back. But Tom is a law student. Just as he did when confronted by the men with the guns on the bridge, he confidently reminds DOE officials of his rights.

“You can use the legal route to get them back,” he says.

They never follow through, but it doesn’t matter anyway. Tom makes copies and shares them with friends.

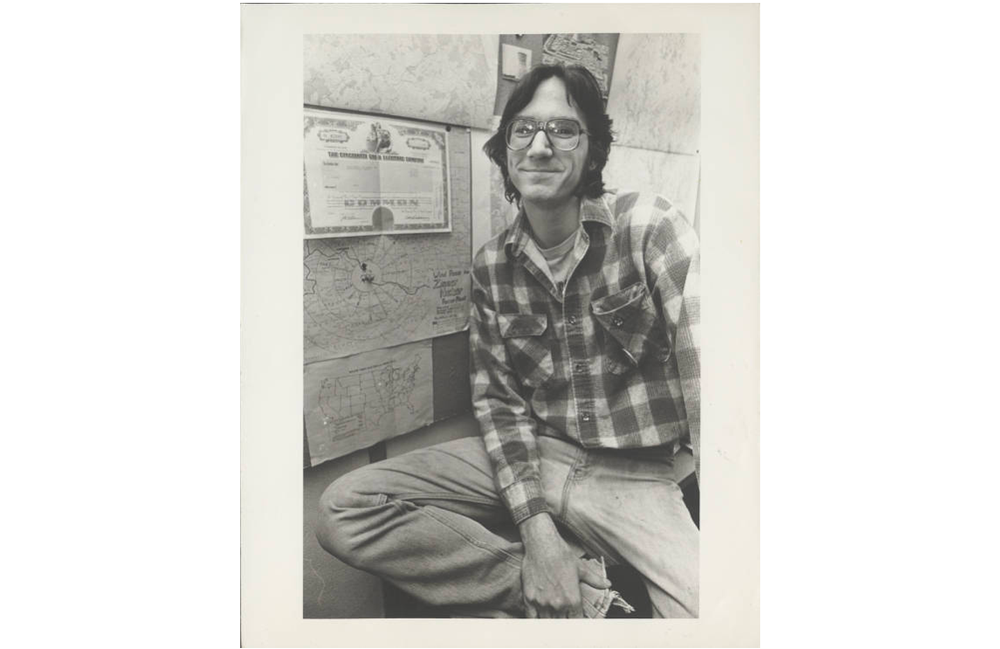

An excerpt from a CARE newsletter that Tom sent after visiting Fernald. Credit: Tom Carpenter.

“The cat was out of the bag,” he says.

Tom makes two more trips to Fernald that year. He samples the sediment in Paddy’s Run and he walks the perimeter of Fernald with a handheld radiation detector, discovering that two waste-holding silos near the fence are leaking radon gas.

Tom and his colleagues on a subsequent trip to Paddy's Run, circa 1980. Credit: Tom Carpenter

He doesn’t have nuclear launch codes, simply evidence of environmental contamination. Still, armed guards and FBI agents have shown up at his door to confront Tom about his probing.

He doesn’t know the full scope of what he’s gotten into, and the ground-breaking discoveries are still a few years away, but Tom can tell he has picked up the scent of something suspicious.

The first half of 1984 is a microcosm of the entire decade. Progressive change and vibrant pop culture run up against harsh geopolitical realities, shaping the 80s as a time of sharp contrast. The 1984 Summer Olympics are just around the corner, but the Soviet Union has boycotted the event. Culture Club’s “Karma Chameleon” is topping Billboard charts, and Vietnam veterans have just settled a $180 million lawsuit for damages suffered from Agent Orange.

Southwest Ohio is also wrought with change and drama. Ohio Attorney General Anthony Celebrezze is trying to figure out what’s happening at Fernald with the intention of suing the DOE. In March, the Ohio EPA conducted its first hazardous waste inspection, concluding that the plant is in violation of almost every procedure in the rule book.

If Dan Arthur knew about the troublesome inspection, it didn’t stop him from taking a job as an auditor at Fernald in May of 1984. But even the EPA’s damning report couldn’t have prepared him for what he finds when he actually gets in there.

Dan grew up in the Midwestern fields of Iowa. He enrolled in the Army right out of high school in 1970. After only two years, he was granted top-secret clearance to work in the Pentagon’s communications office, a role he kept when he was later stationed in Korea.

When he came back, he went to Iowa for college and afterwards entered a career in production and quality control. He stayed in these roles for several years before being hired by NLO, where he was assigned to work at Fernald.

A stocky, mustached man with slightly receding dark hair, he fits the bill of a tough but intelligent former military man. On the outside, he embodies the position of unforgiving Fernald auditor. But inside, he is thoughtful, well-spoken, and extremely professional. He believes in hard work and chains of command, and neither Dan nor NLO has a reason to believe this will falter.

Yet, he finds himself being tested from day one.

Dan drives up to the gates, passing the guards, maneuvering down the road as it cuts through a small patch of trees before opening up to a grassy field. From there, Dan can see the facility clearly.

An aerial view of Fernald, with large production plants to the right, and waste pits and silos holding the worst waste in the background. Credit: U.S. Department of Energy, United States Government via Flickr.

He sees the tower that Tom and Lisa have peered at only from a distance. He sees the concrete smoke stacks jut out from behemoth factories, blowing smoke into the late spring air. He can’t yet see the monstrous waste pits or silos at the back of the facility, which hold the worst of Fernald’s toxic product, but he’ll soon encounter them.

The dozens of buildings that make up the plant — factories, administration, cafeterias, and more — are not spread evenly throughout the thousand-acre facility. They are conglomerated on 130 acres in the center, a miniature city of concrete, surrounded by armed guards amid Midwestern crop fields.

A close-up photo of one of the production plants, where uranium was purified and processed into tubes. Credit: U.S. Department of Energy, United States Government via Flickr.

Dan parks his car and strolls toward the buildings, leaving the grassy fields and trees behind him. Stepping into their shadows is like stepping back in time. The 1950s had never left Fernald. Buildings are in disarray, silos and smokestacks crumbling, and metal barrels leaking yellow-grayish uranium sludge strewn across open pads in between structures. Workers exiting production plants where they handle the uranium walk past Dan without protective gear. Dan is in the midst of an industrial monstrosity on its last breath, with dust and dirt swirling through the air, and infrastructure that looks ready to collapse.

Barrels leaking uranium waste "sludge" onsite at Fernald. Credit: Graham Mitchell.

A railway runs through the center of the buildings, and Dan will soon get accustomed to hearing trains screeching through the site all day long. Fernald contains nine different production plants, which are the largest buildings on site. They are all responsible for different steps of the uranium purification and reclamation process, and all churning out radioactive waste.

Dan makes his way to the laboratory building, where the Quality Assurance Department is housed. He walks through a radiation scanner that looks much like the standing, rectangular metal detector you walk through before entering a stadium.

The workers handling radioactive material walk through these detectors multiple times a day, but that doesn’t necessarily stop radioactive cross-contamination. Raw uranium metal is not the only source of poison within Fernald.

As he steps into the laboratory building, Dan can barely believe the sight. A yellow-gray dust is swirling around. It clings to every surface. Bookshelves, cabinets and tables. In some places, it’s a quarter-inch thick. Footprints are tracking it on the floors. Contaminated coats and shoes are strewn across coffee tables.

Various chemicals result from the process, including UO3, uranium trioxide. Credit: U.S. Department of Energy, United States Government via Flickr.

And Dan understands that this is not just regular dust. This is radioactive uranium dust.

There are no radiation monitors, no working evacuation alarms. It’s lawless. Dystopian. Wilder than he ever could have imagined.

Dan can see that the contractor, NLO, is failing miserably. But Dan is a hard-working man, and Tom believes that, at least initially, Dan thought he could help both the plant and his fellow workers. So despite what he sees on his first day, Dan decides to stay at Fernald.

Government officials aren’t the only ones who notice Tom’s press release in 1983. Anti-nuclear activists like CARE begin putting pressure on Fernald and other nearby facilities to be more transparent about their operations. On the 38th anniversary of Hiroshima, they stand in protest outside the plant.

The media catches on, too. The public begins asking questions about the secrecy at Fernald, and the Ohio EPA gets permission to investigate. In March of 1984, EPA officials are allowed on-site to conduct a hazardous materials inspection.

It’s the first time any outside agency, state or federal, has inspected Fernald, and it fails miserably. The EPA finds storage barrels leaking, faulty filtration systems, and groundwater contamination.

Eight months later, a bag in the filtration system breaks and as alarms begin to blare across the plant, a plume of uranium oxide dust — nearly 300 lbs — releases. Workers hear the alarm, but many ignore it, suspecting that it’s just a malfunction.

The plume is so large it can be seen from town. From her house down the road, Lisa watches the dust billow upward, rising above the treeline. The cloud becomes impossible to ignore. It prompts the Cincinnati Enquirer to begin investigating Fernald’s pollution, and it gives the town something it hasn’t had before: a reason to listen. People begin to wonder whether the activists who have been warning about Fernald might be right.

Lisa feels her anxiety rising. She lives closer to the plant than almost anyone else in Ross. If something is wrong, she knows it is likely happening to her first.

She calls her landowners, two brothers who own the property. They say little. But their father, burdened by what he knows, comes to her himself.

He tells her the Department of Energy has tested her well and found elevated levels of uranium. The results were shared with the landowners, not with Lisa or her family, the people drinking the water. Anxiety hardens into fury. A few days later, the Enquirer publishes its story, and Ross erupts.

In her anger, Lisa writes a letter to the DOE, demanding that they inform her of the exact contamination levels in her well and provide her with safe water. The response is that the well water is within safe limits. The DOE uses terms like “micrograms per liter” and “background level” to manipulate the data.

Lisa is a mother and volunteer coordinator at a psych ward, not a chemist. She neither understands nor trusts them. She buys her own bottled water for drinking, but she can’t effectively use it for everything. She still has to wash dishes and bathe her family with well water. The meeting at Crosby Elementary is still a few weeks away, but Lisa knows she needs to do something.

She’s not the only one in town who is frustrated and a community organization forms to start collectively demanding answers. It’s called FRESH, or the Fernald Residents for Environmental Safety and Health. At one of the meetings, a friend suggests that someone should independently test Lisa’s well.

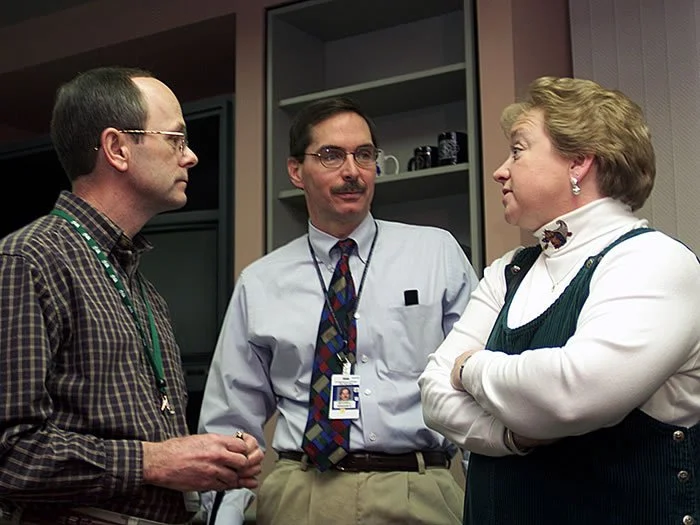

Lisa calls the Ohio EPA, and surface-water analyst Graham Mitchell answers. He is short and slight, with close-cropped light brown hair, a mustache, and oversized glasses. He speaks with care, seeming always to reach for just the right word.

Graham has become the Ohio EPA’s de facto Fernald expert — not by design, but because he is the one who has gathered and organized what little information the agency possesses about the site. He has no idea that Lisa Crawford’s call will alter the course of his career, drawing Fernald into the center of his work.

Since Fernald failed a hazardous-waste inspection, the Ohio EPA has kept the facility on its radar, and Graham readily agrees to Lisa’s request to test her well. In late 1984, he drives from Dayton toward Ross, with plans to sample several private wells that day. It will take weeks for the results to come back, but her well will prove to be the most consequential.

As Graham pulls in front of the Crawfords’ aging white farmhouse, he’s uneasy about what he might find. Lisa is uneasy, too, yet hopeful that this visit will finally bring the answers she’s been searching for.

Lisa and Graham make their way to the backyard, past Kenny’s sandpit, past the pool and the open greenspace that made this land so appealing for their young family. With every step, she sees it differently. Is this home they covet actually slowly killing them?

Graham pulls out containers, similar to the ones Tom used, and takes samples of the water. He can’t stick around. He has more wells to sample. He thanks her, and she thanks him with one of her two-handed handshakes.

A few nerve-wracking days later, Lisa receives a letter in the mail from the Ohio EPA. She slowly opens the envelope and scans the letter inside. The feelings rush in, one after another. Terror, confusion, but above all, unfathomable anger. Both the DOE and the Ohio EPA have found high levels of uranium in her well, but while the DOE insisted it was safe, the Ohio EPA has come to a very different conclusion:

“Find another source of water.”

Dan decides to go to his boss. It’s only been a few months since he took the job, but he can’t just ignore the safety and environmental offenses he’s seeing everywhere.

He isn’t used to speaking up like this, but what he sees is just so obviously bad. His building has a particularly thick layer of dust build-up. But when he tells his boss, he’s dismissed.

“There’s only one dust collector and it’s in the basement,” he’s told. “Don’t worry about it.”

Dan is furious. He storms downstairs, his heavy build kicking up dust in his wake. Some of his colleagues follow close behind, curious that someone is asking questions when the culture is to keep quiet. Dan finds the collector in the basement smokestack. The filter is old and clogged.

“Who is responsible for changing this bag?” he demands. His question is met with silence.

Frustrated but determined to resolve the situation, Dan asks if someone knows where the procedures for changing the dust collectors are located. At least he could read them and assign the appropriate employee to the task.

Chemical operator removes a drum lid prior to sampling residues. Credit: U.S. Department of Energy, United States Government via Flickr.

Still, all he gets is silence.

There aren’t any procedures, and there never were. Not only is one dust collector responsible for filtering radioactive materials out of an entire building, but it has also never been replaced or cleaned. It lay untouched for over 30 years, sitting in the basement, ignored.

It’s an unfathomable discovery, and Dan hopes that after revealing it in front of witnesses, it will be quickly resolved. But it ends up taking months to replace the bag. When the day finally comes, Dan makes sure to be there. Accompanied by two superiors, Dan finds himself back in the basement, watching as a worker reaches into the smokestack and removes the cover from the filter. The bag that is supposed to catch uranium dust is so old that it disintegrates into the worker’s hand.

It is hardly surprising that a thirty-year-old bag lacks structural integrity and has therefore failed. What horrifies Dan is what that failure means: uranium dust has been building up inside the lab for years, while more of it slips past the bag and rises directly up the smokestack.

Dan finds that many of the other filters are in a similar shape. All around Fernald, air filters lack replacement instructions and have rarely, if ever, been replaced. Dan knows what this means: For years, likely decades, unfiltered radioactive uranium dust has been escaping into the air. Air conditioning blasts, open doors, and workers moving about are shifting the dust around buildings. Dust that escapes into the smokestack is billowing into the open sky and downwind toward Ross. The workers likely know they are breathing it. But the surrounding community has no idea they’re being poisoned.

At the beginning of 1985, as Dan is uncovering the plant's failures from the inside, Ross is on the brink of understanding the horrors occurring beneath the red-and-white checkered tower. Press releases, groundwater testing, and meetings in elementary gymnasiums are peeling back the decades-long veil of secrecy.

FRESH members pose for a picture at one of their meetings, with Lisa Crawford standing front and center. Credit: U.S. Department of Energy, United States Government via Flickr.

A few weeks before the meeting at Crosby Elementary School, Lisa is asked to step in as the leader of FRESH. The group's founder, Kathy Meyers, is about to have a baby, and she needs to step down. Lisa sees FRESH as a couple of dozen neighbors getting together once a month to discuss protecting their community. But it’s about to grow into something much more powerful.

The front page story in the Cincinnati Enquirer — covering her showdown against the Fernald officials — solidifies her leadership and catapults FRESH and the issues at Fernald into the spotlight.

But the spotlight isn’t always positive.

One night, not long after the meeting in Crosby, she returns home with her son, Kenny, and finds a DOE van in her driveway.

She scurries Kenny to the back door and catches a glimpse of movement near the well. Someone is pulling themselves out of it.

It’s a DOE worker.

“Hey! Excuse me! What are you doing?” she yells after him.

There’s no answer. He runs to the DOE van, and it speeds away.

“It was an angry, bad year,” Lisa says.

Lisa starts checking her rearview mirror more often. She becomes accustomed to steeling herself before listening to the threatening messages on her answering machine. She notices people staring at her, watching her. But none of the external threats scare her like the ones coming from the faucet of her own home.

Lisa starts looking for a new place to live. She finds one, but delays in remodeling force them to stay on Willey Road for a few more months.

In the meantime, her anxiety is growing.

“You guys need a lawyer,” Lisa’s boss tells her one day. “I have a really good friend who does class action lawsuits, and I want you to call him.”

Two days later, Lisa and Ken are sitting in the offices of attorney Stan Chesley. In town, Chesley has a bit of a reputation as an ambulance chaser, so Lisa is a bit hesitant.

But he didn’t chase us, she thinks.

Lisa wants to know exactly how much uranium and other chemicals are contaminating the town and she knows she’s not going to get it out of Fernald by politely asking. So she and her husband agree to be lead plaintiffs in a class-action lawsuit that also names 12 of their neighbors. Chesley files it against the DOE and NLO.

Momentum is building. People now know that pollution is happening. But FRESH, with Lisa at the helm, wants to know what harm it has caused. In the middle of 1985, FRESH starts compiling health histories.

Members spend months asking anyone who lives within five miles of Fernald to privately share instances of cancer or sudden sickness and death. FRESH member Edwa Yocum, with short, light hair, glasses, and a similar intensity to Lisa’s, keeps track of these in a notebook. One night, at FRESH’s monthly meeting, Lisa and Edwa decide to lay it all out.

Edwa’s husband brings a large map of Ross and they start placing pins at houses where people have been diagnosed with cancer. All night they work, combing through the notebook and adding hundreds of yellow and red pins to the map. When it’s done, they all take a step back.

Edwa Yocum with the map (left) and a close-up of the map with red pins detailing cancer and sickness cases in the town. Credit (for both): Tony Jones / Cincinnati Enquirer.

A pattern emerges.

The pins follow a clear path downwind and downstream of the Fernald facility. It is unofficial, but still highly effective: a map showing elevated cases of cancer and sickness in the direct path of the uranium escaping from Fernald.

“Holy shit,” Lisa says. “It’s so obvious.”

They begin dragging the map everywhere, shoving it in front of cameras, telling anyone who will listen. Local media outlets are running stories almost daily. And soon, the scandal turns national, as similar nuclear facilities across the country are being exposed by activists like Tom. FRESH is one of the first community-based organizations to form against these plants. Many of its members are moms, like Lisa.

“If you piss off a bunch of women, it ain't pretty,” Lisa says. “It doesn’t end well. Not when they have kids.”

The public pressure begins to work. In 1986, Fernald surprises FRESH with an offer no one expected: a facility tour. It’s the first time any members of the public are allowed inside, even though it’s been a fixture of the community for more than three decades.

Lisa is ecstatic. She asks to bring two things — a camera and a radiation detector. To her surprise, they oblige.

Graham Mitchell (middle) and Lisa Crawford (right). Credit: Fernald Community Alliance.

On the day of the tour, Graham Mitchell from the Ohio EPA joins the group. Lisa arrives with several other mothers from the community, caravanning toward the facility in shared cars. The plant rises out of the flat Ohio landscape like a sealed world — chain-link fences topped with barbed wire, warning signs posted every few yards, guards watching from the gate.

Just before they’re allowed inside, an NLO employee assigned as their guide tries to change the rules. No camera. No radiation monitor.

Lisa doesn’t hesitate.

“Fine,” she says. “Then I’ll walk right back out to the reporters at the fence and tell them exactly what just happened.”

It works. He relents. The gates open. Lisa walks in, camera rolling.

The group is led into production plants and through administrative buildings. NLO calls it full transparency. But Lisa sees many of the same issues that Dan saw on his first day of work. Dilapidated structures, dust gyrating through corridors, workers without protective gear.

FRESH touring the site for the first time in 1986. Credit: U.S. Department of Energy, United States Government via Flickr.

The FRESH visitors wear white lab coats, but notice that many of the workers roll their sleeves up. Their arms are covered in yellow dust and green salt, another byproduct of the uranium purification.

The day is long and drawn out, and Lisa is exhausted. As she’s climbing the stairs in a production plant, her bare hand instinctively grabs onto a railing. She doesn’t think much of it until they exit and Lisa sets off the radiation monitor.

“What did you touch?” their guide asks Lisa angrily.

“Just the railing,” she retorts.

He grabs some masking tape and slaps it on her palm, then quickly rips it back off. The way Lisa understood it, he was removing the radiation with the tape’s adhesive.

“You’re fine now,” he exclaims.

But nothing about this tour has eased Lisa’s fears. As they leave, she goes to the gaggle of reporters camped outside the perimeter.

“It’s really bad, it’s dirty,” she says to the camera and microphones shoved in her face. “I feel like the workers are treated like shit, too.”

Not all of Lisa’s adversaries are officials at Fernald. That’s the cruel math of pollution. The same industry that poisons a place often pays its bills. For some in Ross, the choice felt stark: health or financial stability. And for those afraid of the economic consequences, FRESH wasn’t a lifeline; it was a threat to the town’s largest employer.

One night, Lisa is driving home alone from a FRESH meeting when she notices a red car on her tail. It follows her down her private road, and when they get to her house, she blocks them in at a dead end. Lisa and the other driver both get out of the car.

“You might not want to do that,” the man says in a low, menacing tone.

By now, Lisa no longer fears the intimidation. She has endured death threats on her landline and feels her public visibility offers a measure of protection. Lisa responds with cool restraint.

“Don’t follow me anymore.” She never sees the man or his little red car again, but she knows this is a sign that FRESH needs to get Fernald workers on their side.

The Fernald Atomic Trades and Labor Council Union on strike. Credit: U.S. Department of Energy, United States Government via Flickr.

She knows they share concerns about the health and safety procedures inside the plant. Several workers strike in 1986, seeking better conditions. When Lisa finds out they are picketing, she pays them a visit. But first, she stops at White Castle and places a large order for burgers and coffee.

“You know who I am,” she says as she unloads the meals. The workers are intense, steely. They look back at her skeptically.

“I really think we need to have a conversation,” she tells them. “We're not here to take your jobs. We can help you, we’re not enemies.”

It’s the start of a partnership with union president Gene Branham, an outspoken man with a reputation for being a hell-raiser. He teams up with Lisa and they start sharing resources to pressure Fernald to make changes. They agree that if FRESH shuts down Fernald, they’ll join forces to demand worker compensation.

By now, Tom Carpenter, the law school student who years ago was chased off Fernald property while trying to get a water sample, is a full-fledged lawyer in Washington, D.C. He’s quickly becoming one of the most recognized anti-nuclear activists in the country. A fellow organizer connects him to Gene and the union asks him to come back to Ross and help them file a worker safety complaint on their behalf.

Tom drives over for a meeting. He wants to talk to the workers in person.

“Do any of you feel like you've had adverse health effects as a result of working here?” Tom asks, gazing around the room.

The workers look at one another in silence. Then one stands up. He slowly starts raising his shirt, and as he does, Tom sees a vertical scar slashing down his chest like a zipper. The man says nothing. He just lets the scar — which starts below his throat and ends at his stomach — tell the story.

Another worker stands. And another. And another. By the time it’s done, almost every man in the room has shown him their scars. Tom doesn’t believe for a second that these are merely coincidences.

February is brutal in Ohio. The joy of the holidays has long since passed, and spring’s flowers and sunshine are still months away. What this part of the state lacks in snowfall, it makes up for in bitter cold, bone-chilling wind, and constant grey skies.

Dan Arthur escapes the gloom by working overtime. He’s barely seen daylight in a month. But there is a bright spot: At the turn of 1986, the DOE fires NLO and replaces it with Westinghouse Electric Corporation. Dan is hopeful this will mean real change inside the plant.

One of his first tasks is to collect and organize all of Fernald’s DOE orders — the documents that set the requirements in most areas of operations, including worker protection and environmental reports.

Dan spends hours searching before he finds them in the legal section of the laboratory building. He opens the office door to an absolute mess, one better likened to a teenage boy's bedroom than a government-run nuclear facility. Sheets of orders are heaped haphazardly onto shelves or scattered across tables. Binders piled around the room are unorganized, out of place, and often missing labels. Dan slowly walks into disarray, stepping over loose papers scattered across the dusty floor.

He starts collecting it all up to bring to his Westinghouse bosses, but the process reveals that some orders are blank and others are missing. Even if Westinghouse wants to implement better safety standards, it wouldn’t have proper guidance on how to do so.

Dan later learns that the Legal Department stopped keeping up with DOE orders five years ago. He tells his boss about the mess, but nothing happens.

And Dan has other problems to worry about. Seven months ago, a DOE facility in Washington that received nuclear waste from Fernald complained it was improperly shipped and leaking from the train cars carrying it. Dan was tasked with an audit that uncovered dozens of serious problems and was praised for his work.

CHEMICAL OPERATOR TRANSPORTS URANIUM MATERIAL IN T-HOPPER. Credit: U.S. Department of Energy, United States Government via Flickr.

“This is one of the best audits to come out of Fernald,” his boss tells him. "I have another project for you. You will be working on plutonium-out-of-specification."

"What does this project consist of?" Dan asks.

"You will be at a meeting at 10 o'clock Monday, February the 10th, and we will review it with you," his boss replies.

This will be Dan’s last project at Fernald.

The Monday meeting starts on time.

Dan is surrounded by over half a dozen managers and directors, some of whom are the same men who tried to contain the Crosby elementary meeting fallout. They all make it clear: they want the issue resolved quickly.

Here is the problem:

In 1980, Fernald received a shipment of ash contaminated with plutonium, which, according to Dan, is “the most highly toxic material known to man.”

Two years after it arrived, the plant processed a large quantity of it, but Fernald hadn’t followed any of the DOE’s 20 rules for handling plutonium. A 1985 internal investigation found that the workers who handled the plutonium ash had done so without protective gear, special ventilation, or even basic warnings about the hazards. When Dan later interviews some of those workers, they tell him they didn’t know the ash contained plutonium at all.

What they were handling measured 7,757 parts per billion, over 700 times the safe limit, which is set at 10 parts per billion.

And now, in this conference room, Dan is being told to help cover it up.

Instead of bringing the plant back into compliance, Dan is told by his boss to reduce 20 rules down to eight. Only one of them will have anything to do with worker health and safety.

Dan sees the absurdity in the request, but he also recognizes the urgency.

After the Cold War peaked, Fernald’s production slowed drastically, but now President Ronald Reagan is pushing a nuclear buildup that is rekindling demand. Fernald needs to ramp it up to make quotas. Speed, not safety, is the priority.

“When the inevitable clash between maintaining production and protecting human safety occurs, production, at least at Fernald, has won out,” Dan would later say in testimony before Congress.

In the meeting, he says as much. He calls the proposed rewrite an “unabashed rush job.” Some men agree, but some don’t. To break the standoff, the plant’s operations training manager, Andrew Macaulay, calls Fernald’s site manager, Bill Britton.

“We have two alternatives,” Macaulay tells him. “Review and write a few procedures in maybe a week or two, or rewrite a greater number more thoroughly.”

Britton decides two weeks is plenty.

Dan knows it’s not. Even two months would be barely enough. But the deadline is set. Dan now has eight days to write procedures and six days to train the workers who will handle the most toxic material on earth.

Four days later, another meeting is held. Officials pressure him to sign a hastily-drafted health and safety memo that he didn’t write. He refuses. It’s inadequate, he says. A few days later, Dan is again called into a meeting to check on the procedure status.

Before the meeting begins, Dan pulls Macaulay aside to ask how much he actually knows about the plant’s history with plutonium.

“You know, they processed plutonium here without any special precautions in 7,757 parts per billion," he whispers to Macaulay.

“It is all history,” Macaulay replies coldly. “It has nothing to do with this project."

It’s a moment of realization for Dan. First, Macaulay is woefully oblivious to the weight of his position and, willfully or not, ignorant about the operations at Fernald. Second, he doesn’t care to change these things.

The meeting begins, and Macaulay demands that the procedures be signed off on within 24 hours. Once again, Dan refuses. The procedures are still entirely inadequate to protect the workers.

There’s silence. Dan stares at the officials as they stare back. His conscience won’t let him bend to their demands. When it becomes clear they won’t budge, Dan walks out of the room.

Things spiral quickly from there. Dan requests a transfer to another department, but it stalls. Then he gets sick, and his boss accuses him of failing to properly call out of work. Then they start scrutinizing his overtime. They want more hours. And then comes the letter.

His boss walks in and hands it to him without a word. Dan opens it. The letter questions his commitment to the plutonium project and says his actions put his future with the company “in doubt.” Dan checks his timesheets and realizes someone has tampered with them. He recognizes what’s happening. He’s being set up.

The next day, Dan’s sitting on an exam table. It’s supposed to be a routine appointment, but nothing is going as planned.

“You need to go to the hospital,” his doctor tells him.

Anxiety, stress and fatigue are taking a toll on his body, his doctor says, but when he arrives at the hospital, he’s admitted for a bigger problem. Dan has a tumor.

Three days later, he resigns from his job at Fernald.

A gaggle of reporters crowd the Cincinnati airport terminal as Lisa steps out of her car.

Ken helps her out, and as cameras snap photographs, they make their way inside. It’s a big day for the fight against Fernald, and the media knows it.

Ohio Representative Tom Luken, who’d been at Crosby Elementary School that fateful night, had been making noise in the halls of Congress about Fernald. He’s trying to change the DOE's ability to self-regulate, calling for more environmental oversight. He wants Lisa to provide testimony.

As she walks to the gate, her anxiety wells up again. But not because she’ll be speaking to Congress. Lisa is taking her first airplane ride.

“I’m scared to death,” she tells her husband as her boarding group is called. He answers with gentle reassurance.

A flight attendant escorts Lisa to a first-class seat, paid for by Congress. A bright 6-year-old boy sitting nearby looks up at her and immediately asks her name.

“Lisa,” she replies, her voice tight with nerves.

“It’s okay, Ms. Lisa,” he says cheerfully. “Don’t be scared.”

She nods and tries to calm herself down as the plane begins to taxi. As they take off, the boy looks out the window over the nearby Ohio River.

“Wouldn’t it be cool if we landed in the water?” he wonders aloud.

No! Lisa thinks agonizingly, before shutting her eyes. Luckily, it’s a short flight.

She delivers her testimony about living downstream of Fernald. Luken’s proposals are ultimately shot down, but it gets the ball rolling on the federal level, and Congress doesn’t have to wait long before accusations against Fernald show up again on Capitol Hill.

It’s a hot afternoon in the summer of 1986. Tom’s phone rings. On the other end of the line is the reporter from the Cincinnati Enquirer who has been covering Fernald for months.

She tells Tom that a former Fernald employee has contacted her, identifying himself as a whistleblower. His name is Dan Arthur.

At this point, Tom is working for the Government Accountability Project, a non-profit that represents whistleblowers who want to speak out against the federal government. His work is well known. The reporter immediately thinks to connect him to Dan.

A few days later, Tom flies to Cincinnati.

Dan strikes Tom as a man with the meticulous nature one might expect of an auditor. Dan invites Tom to his home and shows him the mounds of paperwork he’s kept from Fernald: copies of all the audits, letters, and procedures detailing the grievances he hopes to share publicly.

Tom is amazed by all of the evidence.

Dan tries to retain his professional, thoughtful demeanor, but Tom can tell that he is nervous, terrified even. Tom sees what he late describes as a “tortured person” who had his profession torn away.

Tom spends hours with Dan, peppering him with questions, looking for holes in his story. But everything he alleges holds up.

“He was prepared, he was a professional,” Tom later says. “And man, they should never have tangled with him.”

Tom files a Department of Labor complaint on Dan's behalf, and they quickly get a hearing before the House Committee on Energy and Commerce. Before leaving for Washington, D.C., Tom and Dan meet with Lisa at her house.

“He put his life on the line,” Lisa says later. “I was very proud of him.”

They all know the weight of the situation. Lisa and Tom have already done an unprecedented amount of work to expose Fernald from the outside. Now, it’s time for Dan to expose what’s happening inside.

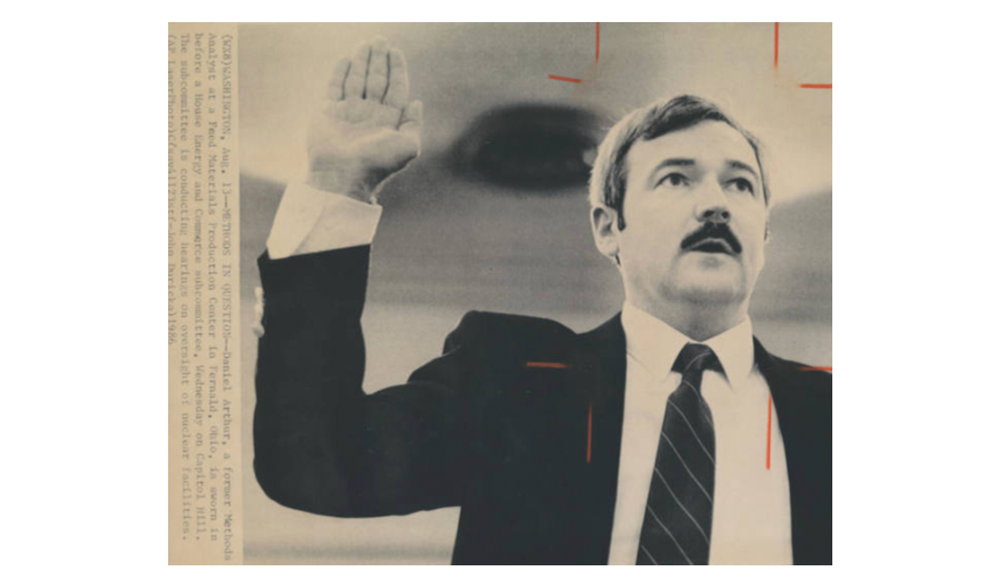

On August 13th, 1986, Dan Arthur delivers his testimony before Congress. He details the misdeeds he witnessed during his two years at Fernald. Representative Tom Luken is there, along with Dan’s former bosses from Fernald. It’s a showdown: the DOE and Westinghouse versus Dan, and Dan is ready for it.

Dan Arthur is sworn in before the House Energy and Commerce subcommittee. Credit: Columbus Library Digital Archive

As his lawyer, Tom watches as Dan showcases his ability to channel his rage into sound, meticulous recountings of the obscenities he witnessed. He answers questions for hours, unflinching at the scrutiny. He gives anecdotes and documentation, rather than relying on untethered emotions to show how corrupt the DOE has become.

When it’s over, Luken praises his testimony. “I haven't heard anything to invalidate or to question his statements,” he says.

It’s only a matter of months before Tom gets word. The DOE wants to settle Dan’s lawsuit out of court.

It’s an incredible moment, and Tom is amazed. On the national stage, the DOE has finally admitted guilt.

Lisa gets a call. It’s 1988, and Ohio Senator Howard Metzenbaum wants to invite her back to Congress. A new piece of legislation is being considered, the Federal Facilities Compliance Act, which will finally give the EPA environmental oversight of facilities like Fernald.

She’s once again called to share her story.

As she takes her seat at the front of members of a Senate committee, she feels the weight of importance pressing down on her. The room is cavernous and formal, its rituals still unfamiliar.

The green reading light clicks on.

Her story flows confidently, thanks to Tom, who spent the night before helping her to refine and rehearse until her words feel steady in her mouth.

She notices Metzenbaum leaning forward, listening closely. A senator from South Carolina, seated farther down the dais, has already drifted off to sleep. Lisa keeps going. Sentence by sentence, her voice unwavered, carried by years of anger, fear, and resolve.

The light shifts from green to yellow. Then to red.

Her time is up.

A staffer moves to stop her, but Lisa continues.

“You paid for me to get here today,” she says, her voice firm. “You paid for my plane ticket. And I feel I should be allowed to finish my testimony.”

There is a pause. Metzenbaum speaks up in her support. The interruption recedes.

Lisa continues.

And in that moment, perhaps more than any other, Lisa Crawford reveals who she is. Terrified or not, she knows how to stand her ground. She is not merely a housewife, not just a woman from a rural town. She is a mother who helped expose, and ultimately dismantle, one of the most dangerous remnants of America’s Cold War machine.

It’s a hot summer day in June, 1989, when Lisa Crawford hears the news she’s been working five years for: Fernald will be shutting down uranium production.

She’s filled with excitement as she begins calling up FRESH members to share the news. They all gather together. Lisa pops a bottle of champagne.

Finally, she thinks. We won.

Years of anxiety and anger start to fade, but they don’t disappear. There are more wins coming, but more fighting as well. Fernald won’t let Lisa go just yet.

Fernald’s story doesn't end with a confession or an apology. It ends the way these stories usually do, slowly, under pressure.

In Washington, the country’s most powerful leaders, including President Ronald Reagan, are now acutely aware of the controversies plaguing Fernald. Tom can’t name the moment the tide turned. He only knows that after years of denials, the Department of Energy begins, inch by inch, to admit what it has done.

In 1987, Fernald folds environmental cleanup into its operations for the first time, opening the gates to Graham Mitchell and the Ohio EPA. In June 1989, President Reagan orders production to stop. That same year, Lisa and Ken Crawford, along with twelve neighbors, settle their lawsuit against the DOE and NLO for $78 million, including the funding for a medical monitoring program that would outlive the headlines. In 1994, the workers’ union wins nearly $20 million more. Dan Arthur’s name belongs in the same ledger of costs, even if the record is harder to summarize neatly.

Tom’s career takes off in the wake of it all. He becomes the kind of lawyer communities call when the contamination is invisible, when the paperwork is buried, when the institution insists it has done nothing wrong. Lisa stays in the fight too, returning to Washington again and again, meeting with President Bill Clinton and Vice President Al Gore, pushing the country to recognize that Fernald was not an accident. It was a system.

Then Vice President AL Gore meets with Lisa during a visit to Fernald. Credit: U.S. Department of Energy, United States Government via Flickr.

And even after the machines power down, the place keeps leaking into the future. Westinghouse shuts operations midstream and radioactive material sits inside the plants for two years until, in 1991, Fernald’s sole mission becomes cleanup. Over the next 15 years, the government spends $4.4 billion to tear Fernald apart and remake it into something the community can bear to look at. The DOE tries to kick Fernald’s long-time workers off the clean up crew, but Lisa sticks to the promise she made years ago over burgers and coffee. FRESH fights alongside the union, and the workers are eventually hired back on to help tear down the facility they spent years fueling.

The worst waste is shipped west. Most of what was made there stays behind, sealed in barrels and buried deep underground. By 2006, officials say uranium levels in the soil have fallen back to acceptable background levels, though the groundwater still has to be filtered. In 2008, the land opened to the public.

Workers stop a leak in a K65 silo (left) and clean out Plant 7 before demolition (right). Credit: U.S. Department of Energy, United States Government via Flickr

A production plant is demolished as part of the site clean-up. Credit: U.S. Department of Energy, United States Government via Flickr

Today the Fernald Nature Preserve looks, at first glance, like any other quiet patch of Ohio. A visitor center. Trails. Wetlands. Birds returning to reeds. When I walked there in 2025, the only obvious wrongness was the low, unnatural mound on the eastern side, a gentle rise in the earth that hides thousands of tons of radioactive material beneath it. The danger is no longer a plume over the treeline. It is an agreement with the ground.

A group of legislators, community members, and environmental workers, after the nature preserve was opened, including Lisa (directly right of the sign) and Graham (behind Lisa). Radioactive material is kept under the mound in the back right. Credit: Graham Mitchell

Lisa visits the preserve from time to time. She meets with FRESH members, still, long after the cleanup is called complete. She is glad the land was given back and encourages her neighbors to use it. But her vigilance has never left her. It has only changed shape.

“When you don’t pay attention anymore is when you get in trouble,” she likes to say.

Fernald is not unique. It is one site in a vast national machine that ran for decades, often in secret, often with the same logic, the same evasions, the same costs pushed onto people who did not consent to carry them. Places like it exist all over the map. In Washington, Colorado, Georgia. What is rare is what happened in Ross, Ohio.

A mother in a pink sweatshirt refused to be managed. A young activist read through the black ink. An auditor would not sign his name to a lie. A community with no playbook became the first to push back.

“It’s my job,” Lisa says. “It’s my lifelong job.”

Sam Norton is a freelance journalist who covers climate change and the outdoors. He's been published in the Wild Ohio Magazine, the Environmental Monitor, and Trails Magazine, and recently graduated from Miami University, where this story idea was first born. When not writing, you can often find him hiking, rock climbing, or skiing.