The Fantastical Life and Lonely Last Days of Michele Hardin

By Jen Golbeck with Gwen Filosa

Michele Hardin’s home, seen from above. Photo / Jen Golbeck

From above Michele Hardin’s house on Sugarloaf Key, the tattered round roof stands out among the lush green of the palms that encircle it. Holes the size of coconuts, ripped open back when Category 4 Hurricane Irma passed over the island in 2017, are not sufficient to ventilate the space inside. The house is condemned. Termites gnaw at the wooden stilts holding it up and there is no power or running water.

Before she died, Michele believed people were trying to rob her so, in the oppressive South Florida summer, where stepping outside is akin to being enveloped in heat and humidity like a heavy blanket, she spent her nights with the windows and doors closed tight, a Smith & Wesson pistol in her hand pointed at the door. A hoard of clothes, old newspapers, and legal documents towered over her frail body as she crept through the narrow paths inside.

In the mornings, she shambled outside. If she was angry, which she often was, she might seek out one of the neighbors on her dead-end block so she could share her grievances. Sometimes it was me. Other days, she would rant in an affected Florida drawl to a neighbor's Ring doorbell camera until the recording cut off. When she needed something, she pushed her dilapidated bicycle down the middle of the road, out toward the Overseas Highway where she searched for food in dumpsters or headed to the foodbank.

Michel Hardin seen on a neighbor’s Ring doorbell camera. Still from video courtesy of Stephanie Boysen

But this was not always her life.

There was a time when Michele Hardin performed under stadium lights as a professional cheerleader, published her opinions in print, held court in Key West society, and reigned as the first Queen of Key West’s bacchanalian Fantasy Fest.

Her property is currently worth close to a million dollars, even with the looming teardown order. If she would only have sold it, she could have lived in comfort somewhere else. But Michele believed the world owed her what she wanted in the way she wanted it, and she was willing to suffer to make her point.

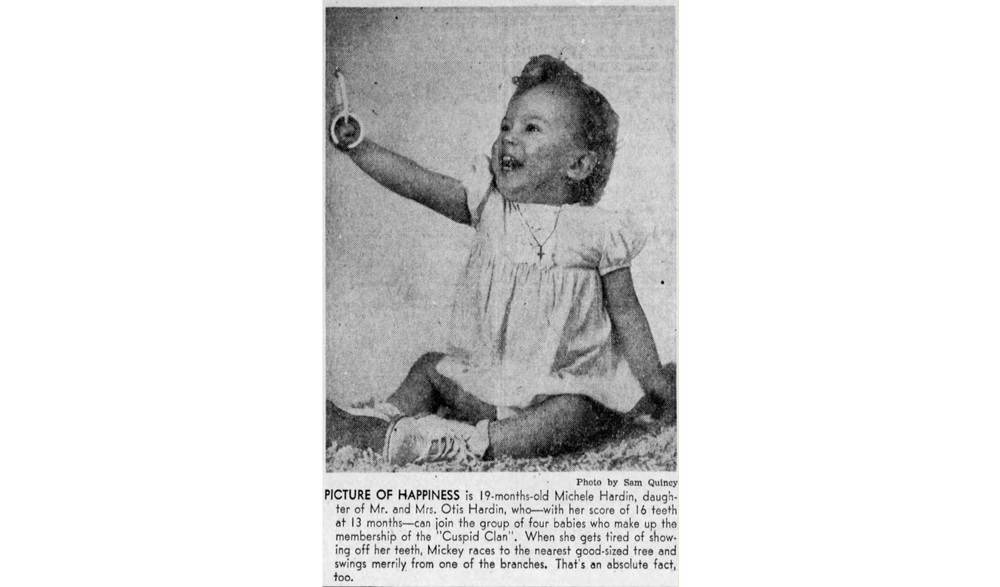

The main living area of Michele Hardin’s home. Photo / Jen Golbeck

Michele Hardin died alone, after years spent living inside a house that was slowly falling in on itself in the heat of the Florida Keys. How she arrived there, from a life marked by attention, glamour, and celebration, is the mystery at the center of this story. In a place where eccentricity is not only tolerated, but celebrated, the boundary between chosen independence and quiet abandonment can be difficult to see. Michele’s life and death sit uncomfortably on that line, forcing a reckoning with what it means to refuse help and what it costs when no one insists.

I met Michele in the spring of 2020.

The Florida Keys, a long, narrow chain of sub-tropical islands, are separated from the mainland by an 18-mile stretch of pavement that cuts through the edge of the Everglades, emerging in Key Largo. Key West is still over 100 miles away down this, the Overseas Highway. During the day, the unreal turquoise water glitters on either side beneath deep blue skies. At night, it is so dark that the Milky Way sparkles in a clear arc across the black heavens. The further travelers venture down the Keys, the lonelier it becomes. For some, the isolation is so disorienting that the road has developed a reputation as "haunted".

The highway would normally be busy with spring break traffic but in 2020, it is eerily empty. The police set up a blockade, cutting the Keys off from the rest of the world in the hope of limiting the spread of Covid-19. Nearly 2,000 tourists are turned away in the first week; only residents are allowed in.

Michele Hardin, 73 years old, loads her cats into her old white sedan, leaves the condo she inherited from her mother in Palm Beach —- now in foreclosure — and heads south. It is a long, final journey down the abandoned highway to her rotting house across the street from my own on Sugarloaf Key.

I had heard about her from neighbors. Stories of how she called Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) on a beloved Hispanic neighbor because she didn't like him repairing the house he was living in; how county officials were afraid to visit to enforce rulings; how there were raccoons and termites infesting her house. I had only known the house as empty, a place the realtor had apologized for when we were purchasing our own, a dark, hulking, damaged shell that loomed silently in the night.

I hoped for the best, but problems followed soon after her arrival. She spied on us — me, my husband, and our dogs — stopping me on the street to tell me that she heard us talking about her or to comment on what she saw us doing in the yard. Her rants grew paranoid and aggressive. In one encounter, she told me she knew the "truth."

"When you moved in, I knew right away why you were here," she said. "I saw your picture in the paper the day before. You're hiding out."

"I don't think that was us, Michele."

"Oh, it was you alright," she said. "I saw that story about how you kidnapped that little girl from Portugal and brought her to South America. My family is the royalty of South America, so I should know. Not that they're helping me much now."

"That wasn't us, Michele. I've never even been to Portugal."

"Well, do you have a doppelgänger then? Both of you? I still have the picture from the paper! I know it's why your husband doesn't want you talkin' to me!"

"Well, why don't you get the article and we'll look at it," I said.

"Fine!" she barked. "I'll find it in my papers and I'll show you!"

But of course, she never did.

We put up a privacy hedge to block her view, but it did little to help. She would wait for us to step outside, haunting us like a ghost with her frail body draped in an oversized T-shirt, her untamed, long white hair swirling around her gaunt, sun-weathered face. She pointedly told me about her gun. I started waiting until late at night to walk my dogs and check my mailbox.

Not all of her actions feel dangerous, but she is always insistent. She catches me out at the mailbox one night and insists for 30 minutes that I need to restore a "grotto" that could be found somewhere along our little stretch of beach that faces Sugarloaf Sound.

Another day, I return from a long run under the oppressive sun of a 2020 summer, my skin grainy with crystallized salt that I had sweated out and sunscreen stinging my eyes, and she complains loudly to herself about how the only reason I wear headphones is to avoid talking to her. Another time, she stops me as I am driving away, stepping in front of my Jeep as I try to pull onto the street. With no other choice, I roll down the window and she spends 10 minutes explaining that I, a 45-year-old woman who runs a 12-minute mile on a good day, need to quit my job and start training for the Olympics. She takes to calling me “Miss Olympiad,” a habit of assigning nicknames that her friends tell me she has had all her life.

She has also renamed our dogs.

“I saw Red Baron running away from your husband when he had them outside today,” she tells me.

“His name is actually Guacamole,” I tell her, irritated at both the name and the fact that she is spending her time watching us go about our lives.

“Red Baron is a better name,” she says. “That’s what you should call him.”

Michele is a dog lover and is fascinated by our many golden retrievers. She tells me, with tears in her eyes, about losing her beloved rescue who she had named Happy Dog. He is buried in her front yard beneath a shrine, but when she tries to show me the spot, she can not find it in the overgrowth. When one of our dogs — a hospice case we had taken in from a rescue group and named Manchego — passes away, she leaves a sympathy card in our mailbox.

I can see in all of these calmer interactions that Michele is trying to be friendly, but it still feels menacing. I keep my distance. Her inability to understand or respect our time and boundaries, and her unpredictability and quick flashes to meanness or paranoia, make it impossible to connect.

The central mystery of Michele’s life is how she ended up living like this when, it seemed, she was destined for something more.

She could have been an heiress.

Michele’s grandfather, Otis Hardin, was an adventurer and builder who was instrumental to Florida’s expansion in the early 1900s. On a flat-bottom boat, he surveyed much of the southeastern Everglades and led the charge to drain the land for building. His construction company was instrumental in building the Tamiami Trail, a road that crosses the Everglades connecting the Atlantic Coast to the Gulf Coast, earning contracts that would be worth hundreds of millions of dollars today.

In 1929, Otis was heading through Santa Fe on his way to Mexico as part of a new mining business venture. Late on the night of Tuesday, May 28, as he was driving down a dark highway, his car overturned. His wife escaped unharmed, but Otis was killed. He left behind two children: a daughter, Marion, and a son, Otis Jr. Otis Sr. was only 45 and in the prime of his career. He was incredibly successful but not yet old enough to have amassed a fortune that would sustain his family for generations.

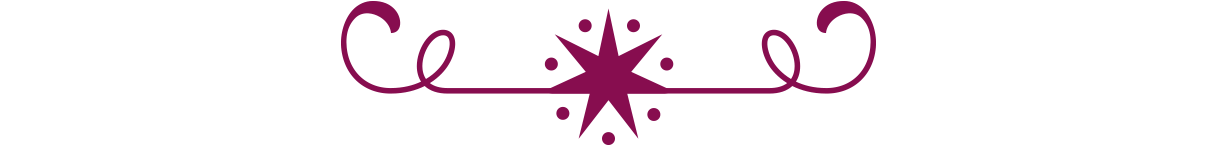

Fifteen years after his father’s death, Otis Jr. would deploy to Europe to fight in World War II . He returned to Palm Beach as a Sargent with three medals and a new bride from France, Clarinda. Michele was born to them in 1947 and got her first taste of fame at 19-months-old. A quarter page of the September 5, 1948, Palm Beach Post was dedicated to celebrating that Michele had a lot of teeth, naming her one of the "Cuspid Clan," alongside a photo of her as a smiling baby.

Michele Hardin at 19-months-old in the Palm Beach Post. Photo / Sam Quincy

Her parents eventually divorced, and Michele stayed with her mother and half-brother, Ralph. Michele’s mom worked in restaurants, as a teacher, and as a journalist, writing for the Palm Beach Times. Michele attended Catholic school in Palm Beach before going on to the University of Florida. She moved to Long Island after graduating and was briefly engaged to a classmate in 1970, but the wedding never happened. She was working as a schoolteacher, studying at SUNY Stony Brook on Long Island in New York, and moving along the path toward a quiet, happy, ordinary life.

Then, in the mid-1970s, everything changed.

In Chicago at the height of the disco era, Rush Street was the center of the city's nightlife. On the brightly lit avenue, the blade sign for Faces outshone all the others. Inside, the private club was crowded with celebrities drinking champagne and dancing on the light-up floor, bubbles swirling around them. Michele was 31-years-old, slim with killer legs, her blonde hair big, feathered, and curled away from her face. She would waltz up to the door with her friends and the bouncer would wave them in. They wouldn't pay for a drink all night.

The Faces nightclub on Rush St. in Chicago. Photo / unknown

Later, when she was home in her apartment, gliding across the white shag carpet, she might pour herself a martini from the white and silver bar perched in front of a large bay window, Chicago's city lights twinkling in the darkness behind it. In her bedroom, the walls tiled with mirrors, she would pick her way around scattered clothes, platform shoes, and big earrings. In the apartment directly below her, and in many more throughout the brick tower, she was surrounded by her friends and fellow Chicago Bears cheerleaders — the Honey Bears.

Michele was chosen as one of 28 women to join the NFL cheerleading squad in 1978. Though they were only paid $15 per game, they made hundreds of dollars a week working events and lived glamorously. Michele even talked one of the Faces employees into picking up the cheer squad from their apartment building in the club's limousine and driving them to practices.

Michele Hardin in her Chicago Honey Bears uniform in a promotional shot. Photo / Michele Hardin’s Personal Collection

She failed to make the squad in 1979 but was not deterred. She went to the Chicago Bulls and proposed that they start their own cheerleading team. They agreed, and Michele became the manager and coach of the Luvabulls — a team that is still cheering today. At the same time, across the country in Los Angeles, Paula Abdul was cheering as an L.A. Laker Girl. It was a moment when professional cheerleading could open the door to fame and success. Michele was beautiful, successful, socially connected, ambitious, and living in one of the greatest cities in the world.

But beneath the glamour and achievements, were foreboding undercurrents. She was beloved by her friends, but her relationships had challenges. She was funny and supportive but also controlling. "You could not argue with Michele," recalled her Honey Bears teammate Renee. "There were parts that were very hard for me to deal with."

A Luvabulls team photo, including Michele Hardin, lies in a corner of her home on Sugarloaf Key. Photo / Jen Golbeck

Her bids for attention were sometimes desperate and inappropriate. At her close friend Greg's wedding, she interrupted the formal photos and called him to the dance floor. There, she and a group of other cheerleaders performed a dance for him as friends and family looked on with a mix of amusement and horror. It took Greg 45 minutes to find his upstaged wife crying in a dressing room. "She never forgave Michele for that," he said.

A cheerleading practice photo lies among boxes of photos in Michele Hardin’s home on Sugarloaf Key. Photo / Jen Golbeck

By the mid-80s, and after an unsuccessful audition for the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders, Michele's native Florida was calling. She returned to Palm Beach where she had grown up. In 1987, 40-year-old Michele married a 41-year-old boat captain from Key West in an underwater SCUBA ceremony on Valentine's Day, eight days after his divorce from his third wife was finalized.

The marriage didn't last, but Michele made the Keys her home. She bought the round house on Sugarloaf Key and christened it "Michele's Tree House". A coconut palm and Sea Grape flanked her driveway and she parked her white convertible out front. She hobnobbed with the Spottswoods, a prominent Key West family, and worked hard, writing a social column called "Dahlings!" for the Key West Citizen and covering events for the local paper. She hosted a public access TV show, and pretended to play instruments out at Looe Key Reef in the Underwater Music Festival every summer. But nothing showed her place in the community as clearly as her coronation.

A photo of Michel Hardin at her home on Sugarloaf Key. Photo / Michele Hardin’s Personal Collection

If Mardi Gras and Halloween had a love child, it would be Key West's Fantasy Fest. The 10-day festival in late October is a costumed, sexually charged street party where revelers — sometimes dressed only in body paint — parade through the streets. The more adventurous gather for late-night sex parties in the back rooms of clubs or in people's homes.

In 1989, for the first time, Fantasy Fest selected a royal court. Candidates attended social events and raised money for a week, jockeying for votes. Michael Mell, a Key West bookkeeper, was a candidate for King. He told the Miami Herald that for his costume, he was dressing as a psychiatric inmate at the Key West hospital. Michele would become an inpatient at that hospital 35 years later.

But not yet. Michele ran for Fantasy Fest Queen and won. Like all the candidates, she helped raise money for AIDS, a disease that claimed the lives of over 1,300 Keys residents. As her obituary would later say, Michele was someone who fought for people who she felt "had been left behind by the system."

She debuted in a floor-length, cleavage-baring silver sequined gown with chandelier earrings, and an honorary red cape, bedazzled scepter, and a puffy fabric crown. The King, David Etheridge, stood next to her in khaki slacks and a black Fantasy Fest T-shirt. Michele looked radiant. She was happy.

Michele Hardin and David Etheridge as Queen and King of Fantasy Fest in 1989. Photo / Michele Hardin’s Personal Collection

After she made this socialite splash, Michele effortlessly waltzed into the island’s top social circle. Through the University of Florida alumni club, she met Andrea Spottswood, a member of one of Key West's most prominent families.

Andrea was fascinated and drawn to Michele. She had never known anyone quite like her: larger than life, unpredictable, absolutely determined, and unbothered by self-doubt. They became close friends, with Michele pulling her laid-back friend along on fun-loving, often over-the-top escapades.

In 2008, Michele insisted they go see the Sex and the City movie at Key West’s Regal Theater. Seated inside,, Michele opened out her tote bag to reveal that she had smuggled in Cosmopolitans, the signature drink on the show. Michele poured one for each of them to sip as they watched Hollywood’s glamorous take on Manhattan dance across the screen.

Andrea loved their time together even as Michele’s struggles became more visible. Throughout Michele’s final years, Andrea would still bring her along to the University of Florida’s alumni football watch parties, though other guests began to roll their eyes when they would see Michele come in. “To be perfectly honest, a lot of people didn't get along with Michele,” Andrea said.

The front of Michele Hardin’s home on Sugarloaf Key, 2024. Photo / Jen Golbeck

In the summer of 2023, the Florida Keys are baking. The sun has warmed the shallow waters until they feel like bathwater; the ocean breezes only move the air around. For weeks, Michele has been coming to my gate every day with a tattered two-liter plastic bottle and waiting for us to come outside so she could ask us to fill it. At first, she says it was because she thinks her water is contaminated. Eventually, it becomes clear that her water has been cut off.

Her power is off, too; the half-strand of Christmas lights draped across the railing of her rotting balcony have been dark for weeks. The heat index hovers around 110º, and I worry that she will die.

I start bringing her more water. Several times a week, I use my garden hose to fill orange Home Depot buckets pilfered from my hurricane supply closet, load them onto a cart, and slowly trundle over my gravel driveway to her house. I dread these interactions. They can go on for an hour, with Michele insisting I listen to her rants about the government, berating me if I tell her I have to go back to work.

She asks me several times to run a hose hundreds of feet from my house to hers, or at least to the edge of the street, but I refuse. Eventually, I call the Florida Keys Aqueduct Authority and discover that the water was turned off simply for non-payment. I charge the $400 balance and tell them to anonymously bill me every month. I do it to help, but also to save my own mental health. Michele's disregard for my time, privacy, and boundaries is more than I can handle. I am filled both with relief and guilt when the restored water reduces our encounters. The bill for that water was over $750 during her last month in the house; she must have had a hose running continuously for the entire month to earn that, but I have no idea why she would have done that.

The inside of Michele Hardin’s refrigerator. Photo / Jen Golbeck

My husband and I have a tense discussion one night after I find a carton of milk in our fridge. Michele had caught him out in the yard after she returned from the food bank. She picked up the milk there but, without power at her house, she has nowhere to store it. She asks if she can keep in our fridge and, inexplicably, my husband had agreed. I remind him that she has turned against every person on the block who has tried to help her in the past.

"She is going to want it at some point and she will stand there at the gate demanding we come out. She's also going to start asking us store other things for her. If we don't give it to her when she wants it, she is going to accuse us of stealing it. She will be here constantly asking for things, interrupting our work."

I think about our neighbors down the block who had tried to help, which led to her visiting their front door sometimes 10 times a day until they had to insist she stop coming. "We cannot work as her refrigerator. We need to hold boundaries with her."

Though he struggles in the face of her persistence, my husband eventually tells her we cannot keep her refrigerated items. Our neighbors, who spend a lot of time away, tell us later that they discovered she had started sneaking over to their house and putting food in their poolside outdoor fridge.

Other neighbors start bringing Michele food and supplies. Some make extra portions of dinner and offer her plates. One buys her cases of bottled water, but because the sun shone on them as they rested in her yard, she decides they are contaminated and orders the neighbors to take them away. We all try to get her power turned back on, but fail.

A few months later, she stumbles out of her house and down the street. She tells the people she encounters that she has not been out of bed in four days. Her legs are swollen and pocked with oozing sores and she smells of incontinence and infection. They feed her and offer to take her to the hospital, but she refuses. She limps back to her hot, dilapidated home alone.

The time has come for Michele's family to step in to take care of her, but there is no one to do it. Her mother died in 2008 and her half-brother in 2016. According to Michele, she is alone in the world.

Except this isn’t true.

Months after her death, I spot a car parked in her yard. The visitor is Patrick, Michele's cousin on her dad's side. Michele never mentioned this part of her family, but someone in the county has found him. He is beginning the long process of settling Michele's estate.

We talk for almost an hour. He remembered seeing Michele and her mom a few times when he was very young, but he had not known her as an adult. Michele had never mentioned this side of her family, and none of them had any idea about her struggles; she was just one of those distant family members who had drifted away. He seems shocked by the state of the house and at the stories of her final years.

"We would have taken care of her," he says of his family. "I wish she had reached out. We had no idea."

If she hadn't insisted that she was alone, those of us trying to help her would have reached out to them, too. Instead, as Michele's situation becomes more perilous, I call Florida's Adult Protective Services about her. They send someone to check in, but it backfires spectacularly. Because of that visit, Michele begins telling people that the government is spying on her.

She sees conspiracies and injustice everywhere. When her next-door neighbor installs a fence, I wake up to her screaming in the street at the contractor installing it, accusing him and the neighbor and the county of stealing her property. For weeks, she tells me repeatedly about how everyone is working together to take her land.

She finds a set of car keys in a popular swimming spot and decides their owner was murdered by the mob, their body dumped in the Atlantic Ocean. She preserves them in a plastic Tupperware container and tells me over and over that she is trying to get a meeting with the Monroe County Sheriff to share this "evidence."

Michele is incensed when the county orders her to trim her trees that hang into the street.

With her permission, neighbors trim them back for her, but she is not appreciative. She takes this act of kindness as another attempt to steal her property. She reinforces the chains across the street in front of her lot with a barricade of trash cans, sets up a stool, and sits there all day, on guard for anyone who approaches the property line.

The neighborhood worries about Michele, but feels powerless. She is volatile and mean, and our calls to the police and ambulance for wellness checks never amount to anything. At block parties, conversation inevitably shifts to her and then to mental illness. Longtime residents often link her paranoia and conspiratorial thinking to her ongoing legal battles.

In 1998, ten years after she bought her house, the county cited her for having an illegal ground-level apartment — something prohibited because of the regular flooding caused by tropical storms. Michele would spend the next 25 years acting as her own attorney, fruitlessly fighting the county. She cared for her mother in that illegal room until her death in 2008, she told me, and she planned to die there, too.

As the years went on, her filings became less coherent. Titles on some of her motions to the 3rd District Court of Appeal include “Motion & Notice , as United States citizen constitution originalist, & right to know, entitles me to truth & disclosure of why, I'm denied, neglected, discriminated without my due process right to know” and “Notice ~ of my fundamental 11th Amendment rights being violated, & added to my already preserved basic 1st, 4th, 5th, 6th, 7th, 8th, & 14th Constitutional rights remaining in ongoing violated victimization, & duly noted in pleads against violated due process rights.”

At one point, in 2020, we had replaced a desk in our house and I brought the old one out to the curb. She hurried out of her house, picking her way through the broken pieces of a table, an old tire, and plastic containers strewn through her front yard.

“I could use that!” she cried. “I need it to work on my legal papers.” As I helped her carry it into her house, she explained how she spent her days doing legal research which, I later discovered, based on the binders in her house, was mostly printing out web pages that she hoped could help her win her battles with the government.

Boxes of files in Michele Hardin’s home. Photo / Jen Golbeck

A minor win in the Florida Supreme Court over an administrative error — one that did little but reset the date at which the fines started — only seemed to push Michele deeper into the fight. By 2020, she did not seem to understand the ruling. She told me once that the United States Supreme Court, including her “buddy Clarence Thomas,” had ruled in her favor and allowed her to keep the illegal room. Meanwhile, the fines that had accrued were over $200,000.

The bathroom of Michele Hardin’s illegal ground-level apartment. Photo / Jen Golbeck

As she fought the county and state over the requirement that she connect to the municipal sewer, her septic tank was overfull and raw sewage backed up into her house. Folders with legal filings, binders of website printouts, and loose papers began to accrue, stacked on shelves, in old fruit boxes, and in deep piles on every surface. All were covered with small dunes of frass, the sand-like grit that fell from her termite-infested ceiling. She stopped paying her bills. But long-time neighbors say that the final blow to Michele's sanity had come with the storm.

The primary bathroom in Michele Hardin’s home, with a patched hole in the ceiling. Photo / Jen Golbeck

The calm blue of Hurricane Irma's eye opened over Michele's house on Sugarloaf Key on September 10, 2017. If she were at home, she could have looked out through her round skylight and seen the sun shining above her. The peace over the empty house was brief as the storm spun onward and its 130 mph winds roared back.

Light shines in from the skylight at the peak of Michele Hardin’s home. Photo / Jen Golbeck

The next day, the roof was pockmarked with holes and a large section had been ripped away over the back porch. The deck had collapsed and a palm tree leaned against one side. Monroe County would eventually declare the structure unsafe and post signs prohibiting entry . Michele tears them down when she returns to the house in 2020.

Because Michele did not have a mortgage that required it, she decided to forego homeowners’ insurance. That left her without the money to repair her home. . State programs would have purchased her property outright or torn it down, as state law required given the extent of the damage, and built her a new home at no cost. But, Michele didn't want that. She wanted her house repaired, put back together, not leveled and replaced anew.

The porch landing at the front of Michele Hardin’s home on Sugarloaf Key. Photo / Jen Golbeck

Undeterred by the teardown order, state code, mounting fines, and her own lack of funds, Michele set out to fix her home herself. The damage to the roof was the most critical to repair. Several large sections over a room she used as an office — a space with windows on three sides that let in a beautiful, hazy, dappled southern light — had collapsed in. There was another hole punched in the bathroom ceiling, as though a coconut had been punched straight through it. She patched that bathroom hole with plastic bags and tape. For the office, Michele set out to do some construction herself.

The office room in Michele Hardin’s home sustained significant damage to the roof. Photo / Jen Golbeck

She must have borrowed a ladder to make her way up onto the unsound, round roof. There, standing above all the other homes on the island, she tied a rope around her waist for security and tried to undo what the storm had wrought. It was a precarious mission for anyone, let alone a frail, 70-year-old woman who suffered from bouts of vertigo. Michele did not fall off the roof that day, but she did fail to repair it. From inside her house, the sky is still visible in that room, which now smells of mildew. Pine needles that have rained down from the trees above have cascaded into piles on the desk and floor. The buckets she placed to catch the torrents of rainwater that streamed in during every storm still sit on the floor, full and stagnant. Piles of other unused building supplies — floor tiles, siding, insulation, and lumber — remain stacked under her house, some decaying after close to a decade exposed to the elements. It’s a testament to a determined and stubborn old woman’s love for her home.

The deterioration of Michele's house seemed to track the deterioration of her mind. Over the previous decade, the seam of stubbornness, argumentativeness, and fight that her friends had been able to overlook had widened, swallowing the fun, ambitious, joking part that people loved. Suspicion found its way in and her connection to reality crept away.

Building supplies lie under blue tarps beneath the collapsed back deck on Michele Hardin’s home. Photo / Jen Golbeck

Friends who loved her never lost their fondness for her, but they struggled to stay close. Her Honey Bears cheerleading teammate, Renee, wrote a book about the cheer squad. One chapter of that book was a compilation of personal stories from the sidelines, shared by Honey Bears over the years. Although everyone was limited to sending a few pages, Michele saw this as an opportunity. In 2018, just months after Hurricane Irma, it must have been a relief to have this assignment.

With no internet and limited power in her house, Michele headed off to work at the Key West Public Library. The pink stuccoed building has an arch over its welcoming front doorway and a wide courtyard patio shaded by tropical plants alongside it. There, for weeks, Michele drafted her own history of the Honey Bears and ended up producing her own chapter-length story of her one year on the squad. When Renee and the publishers told her it would not fit, Michele simply insisted they give her a whole chapter all to herself as a solution. Renee chokes up recalling the month she spent trying to reach her old friend for a condensed version as the deadline loomed. Michele refused to let anyone edit what she wrote and, ultimately, it was dropped. Renee remembers the anguish of the decision in the face of her friend’s stubbornness. She also treasures the manuscript, even though it is tinged with sadness.

My next-door neighbor, Anita, shared similar feelings. The women were once close friends, but Michele turned on her, accusing Anita of betrayal for not stopping the county from inspecting Michele’s house while she was away. It was actually Anita who first — correctly — warned me about Michele and, while I thought there was only bitterness remaining in their relationship, I was wrong. In the months after her death, I sat at a long table covered in a plastic checkered tablecloth in Anita’s backyard beside the pool, and asked about her earlier memories of Michele. She reflected fondly on helping her do her hair for a party, and almost bragged about her success. She pulled a tattered copy of Michele’s old business card out and handed it to me to show that Michele had once been ambitious and doing interesting work. When I was leaving that night, heaping leftovers into containers, she asked for the card back. She teared up as she told me, “it’s the only thing I have left of her.” With all the frustration Michele seems to have brought her old friends, the love they had for her as a younger woman — and the grief they had for that lost version of her — was fresh.

A promotional card for Michele Hardin’s work promoting Chicago cheerleaders as models lies among other papers on the floor of her home in Sugarloaf Key. Photo / Jen Golbeck

Andrea Spottswood recalls Michele growing more irritable over time, but she stuck by her. When Michele began alienating others, Andrea still held her friend in her mind as the freewheeling local celebrity who would drive around town in her convertible with the top down, curly hair flying, Happy Dog in the passenger seat with a bandana around his neck and Wayfarer sunglasses resting on his snout.

When Michele returned to Sugarloaf Key in 2020, Andrea and her husband would appear at her house with groceries and clothes. I did not know who they were at the time, but my husband and I saw these deliveries and called them the "resupply missions." Their pink Cadillac would pull up to the overgrown yard, idle there for 15 minutes, maybe half an hour, while Michele leaned in the passenger side window chatting. Eventually, she would carry plastic grocery bags full of whatever she needed into her house and they would drive away. Later, when Michele was in the hospital, they would come by and pick up her accumulating mail.

“I loved her,” Andrea said. “I did love her.”

When people were helping Michele and behaving exactly the way she wanted, she was friendly, even garishly charming. When people did something that she disapproved of, regardless of whether it impacted her, she was quick to criticize. If they denied her what she felt entitled to, she could become enraged. Over time, it seems, those more problematic pieces of her personality took over, fueled by mental illnesses or age or both.

Her physical health deteriorated in that last year, too. After landing in the hospital with an infection, the court declared her unable to care for herself and appointed a guardian.

Her two outdoor cats were left behind. The SPCA could not take them since they were still Michele’s property. Some friends and neighbors come and fill their food bowls and I begin venturing into Michele’s yard to refill their water each day. They often hide but occasionally creep out asking to be stroked and, despite my allergies, I always oblige. While there, I get a better look at how she had been living. The space feels haunted. A garden hose runs up through the underside of her balcony, serving as an outdoor shower. Shampoo bottles and a threadbare towel lay on the ground underneath it, beckoning for a body to stand there. There were magazines, tchotchkes, and construction materials, the remains of uncompleted projects no longer fit to be completed. During one of these visits, I noticed something in the knee-high grass off to the side. I approached and discovered it was a ghost from my own life.

My dog, Hopper, had passed away the previous year from a cancer that had, 18-months before her death, taken her right front leg. She thrived for a year as a tripod, but as the arthritis grew worse in her remaining front leg, she started to struggle to walk. In a desperate attempt to alleviate her pain and forestall the end of our time with her, we ordered her a custom-built doggie wheelchair. This contraption for disabled pets has an aluminum frame that held a sling for her chest and two large wheels in the front. In theory, we could strap Hopper in and those wheels would act as her front legs, taking the weight off her painful elbow and allowing her to push herself around with her back legs. In practice, Hopper hated that thing. We tried everything to get her to use it but she never did more than push herself one time around in a circle and then sit down. It sat unused on our back porch for months, its promise unfulfilled. After we lost Hopper, we put that cart out at the curb on garbage collection day. Instead, Michele had taken it and tossed it into her side yard.

As the community tended to her cats, Michele spent months at Lower Keys Medical Center before being transferred to a nursing home in Key West. Shortly after the move, she caught COVID and passed away. She was 77 years old.

Someone took in her cats. The house remained dark and I stopped paying her water bill. After months without anyone claiming her body, the county paid for her to be cremated.

On December 20, 2024, on a warm, cloudless day, she was one of 72 Keys residents who were laid to rest in the Homeless Persons Memorial Service in Key West Cemetery. A Christmas wreath hung in front of the communal vault.

Carolyn Woodhead of the Florida Keys Outreach Coalition speaks at the Homeless Persons Memorial Service in Key West Cemetery where Michele was interred with 71 other Keys residents in 2004. Photo / Jen Golbeck

That would have been her final resting place if her family had not been found. After a few months of talking to the county, Michele's cousin Patrick let me know he had received her cremains, as well as those of Michele's brother and mother. He is making plans to have the three of them buried together in a family plot in West Palm Beach. The family she had lost will be together in death, reunited by those she had rejected in life.

A wreath decorates the vault for the homeless in Key West cemetery, where Michele’s cremains were interred until her family was located. Photo / Jen Golbeck

The round house still stands across the street from mine, empty and overgrown. At night, a small solar light flickers on along the staircase, the only sign of life. It is easy to see the house as a symbol now — a cautionary object, a ruin — but for decades it was simply where Michele lived, where she made choices, fought battles, and refused to leave. Its slow decay mirrored something else unfolding inside it, though no one could say precisely when stubbornness became danger, or independence became isolation.

Michele’s home, illuminated only by a solar-powered porch light, is seen at night. Photo / Jen Golbeck

Michele did not lack resources. She owned property, had access to medical care, and came from a family that would have stepped in had they known how badly she was struggling. She also lived among people who brought water, food, groceries, and patience long after patience wore thin. And still, none of it resolved the central problem: Michele did not want help as it was offered. She wanted control over her house, her story, her body, her battles, and she defended it fiercely, even when it cost her comfort, safety, and connection. When care is refused, a community is left to choose between trespass and absence, neither of them innocent.

Michele’s life does not offer a lesson so much as a demand: to sit with the discomfort of not knowing where responsibility ends and autonomy begins. In the Keys, where eccentricity is a kind of currency and self-determination is prized, that line is especially hard to see until it has already been crossed. Michele lived on that threshold for years. In the end, she never fully crossed to one side or the other. She remained, as she always had, fiercely herself, while the cost of that insistence quietly mounted.

Jen Golbeck is a writer, photographer, and a professor at the University of Maryland. Her work focuses on conflict of all sorts—war, extremism, unrest, and disaster. She is also the author of the best-selling book, "The Purest Bond: Understanding the Human-Canine Connection". She and her husband rescue special needs golden retrievers and Jen splits her time between Washington DC, the Florida Keys, and New Orleans.

Gwen Filosa is a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist in Key West, Florida. She publishes Key West Newswire -- an insider's look at Key West news, culture and assorted shenanigans.

Before landing in Key West, she was a staff writer at the New Orleans Times-Picayune from 2000-2010, covering the criminal courts, police, and the annual Carnival and Mardi Gras celebrations. She's appeared on NPR national reports and CNN, and was a staff reporter at WLRN, Miami's NPR station.